The story of the American Revolution typically highlights heroic battles, key political figures, and defining moments like the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Yet, behind these stirring events lay an influential force that helped shape public opinion and galvanize colonists: propaganda. Far from being a modern invention, propaganda—defined as strategic communication designed to influence perceptions—was a driving force that sparked collective action. Whether it was the printed word, political cartoons, or powerful symbolic images, propaganda functioned as a unifying weapon in the fight against British rule.

Propaganda emerged as a tool for colonial leaders and everyday citizens to rally support, articulate grievances, and cultivate a sense of shared identity. By analyzing the colonial mindset, the mediums used, and the notable voices involved, we gain a clearer understanding of how propaganda contributed to the American Revolution. This article aims to explore not only the creation and spread of revolutionary messages but also the deep legacy these efforts left in the formation of American political and cultural identity.

Defining Propaganda

In the simplest terms, propaganda is a targeted message aimed at swaying an audience’s opinions or actions, often appealing to emotions and biases rather than relying on neutral, factual accounts. Although we associate the word “propaganda” with negative connotations today, especially in wartime contexts, its application can be both positive and negative depending on one’s perspective. In the period leading up to the Revolution, colonial propagandists harnessed various mediums—pamphlets, posters, speeches, and more—to unify disparate colonial interests against what they viewed as oppressive British policies.

Propaganda can take many forms, from straightforward news articles to outright exaggerations or even fabricated accounts meant to outrage the public. In the colonial context, individuals such as Samuel Adams and Benjamin Franklin understood the importance of controlling the narrative. They knew that if they could highlight the injustices committed by British authorities in a compelling way, they could swing hesitant colonists toward the cause. As tensions mounted, effective propaganda proved pivotal in pushing the population from passive discontent to active resistance.

Colonial Tensions and the Seeds of Resistance

Before we delve into the mechanics of propaganda, it’s essential to grasp why colonists were so primed to absorb these messages in the first place. From the late 1600s through the 1700s, Britain and its North American colonies formed a complex relationship grounded in trade, governance, and shared defense. However, after the French and Indian War (1754–1763), Britain found itself in substantial debt. Eager to replenish the coffers, Parliament introduced taxes and legislation, including the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Acts (1767). These measures infuriated many colonists, who believed they had no direct representation in the British Parliament to advocate on their behalf—fueling the now-famous cry of “no taxation without representation.”

This environment of growing frustration created fertile ground for effective propaganda. Grievances were widespread, yet discontent was not universally shared across all colonies or social strata. Some merchants were more concerned about port taxes than personal liberties, while farmers worried about the cost of goods more than abstract political ideals. Propagandists seized on these varied grievances, weaving them into a single narrative of British tyranny. By linking various local issues—like taxes, quartering of troops, and restrictions on trade—into a broader storyline of oppression, they fostered a sense of unity. Suddenly, a farmer in Pennsylvania could see a direct connection between his hardships and those of a merchant in Boston.

Moreover, the cultural shift in the colonies had already begun. The Great Awakening of the mid-18th century had swept through religious communities, encouraging ideas of personal autonomy and challenging traditional authority. This environment made colonists more receptive to arguments against centralized control. The stage was set for persuasive messages to be embraced by a population ready to assert its own identity and question the status quo.

Pamphlets, Newspapers, and the Printed Word

One of the most potent tools in the revolutionary arsenal was the printed word. During the 1700s, the colonies experienced a significant boom in literacy rates, especially among white men. Newspapers sprang up in major towns like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, rapidly circulating ideas and news. These outlets became an essential channel for colonial voices to broadcast their grievances and spark public dialogue.

Newspapers

Publications such as the Boston Gazette and the Pennsylvania Journal frequently included editorials that criticized British policies. They published firsthand accounts of protests like the Boston Tea Party, ensuring that colonists across the region could read about these acts of defiance. Editors often aligned with political causes, so readers received articles designed to motivate them to take a stand. While factual reporting did exist, sensationalism and partiality were not uncommon, as editors recognized the galvanizing power of emotionally charged stories.

Pamphlets

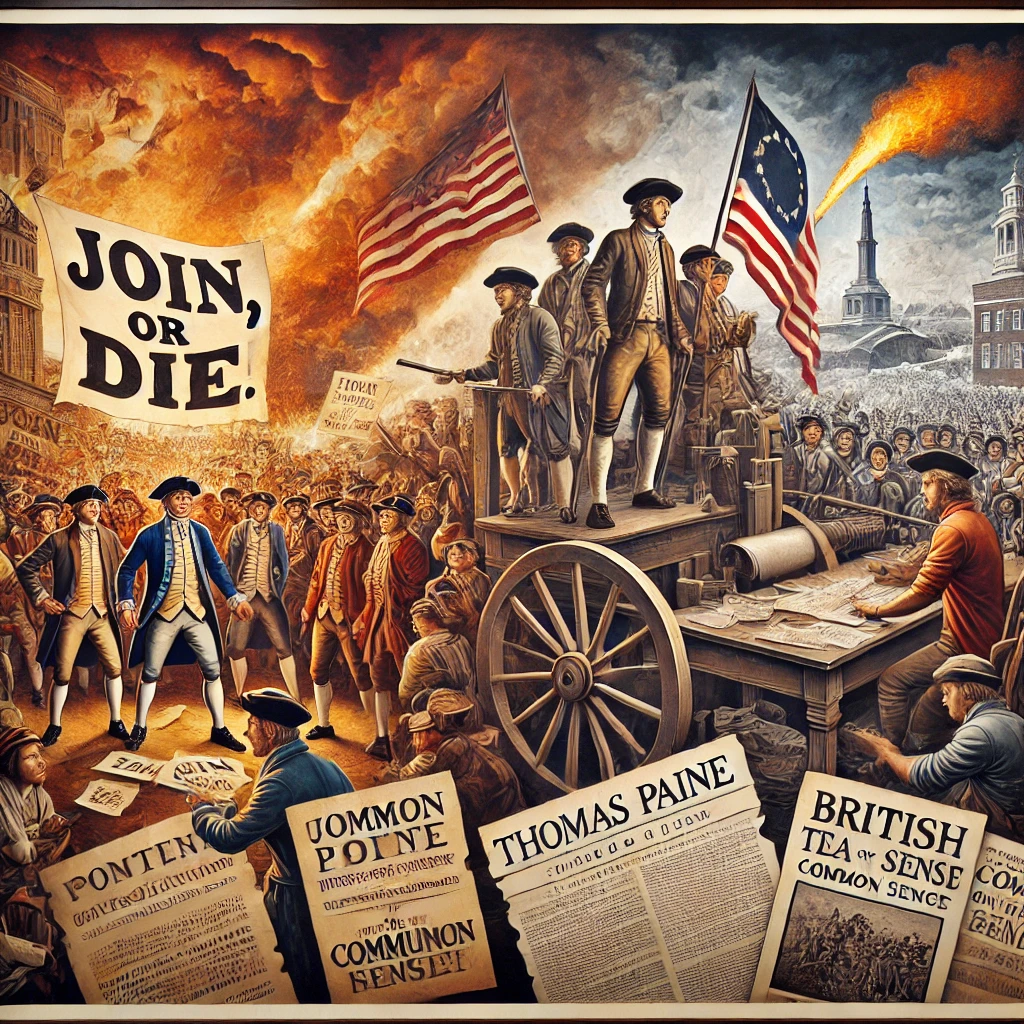

Perhaps no form of propaganda was as influential as the revolutionary pamphlet. These affordable, easily distributed booklets offered a direct way for leaders and thinkers to engage with the public. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, published in January 1776, stands out as one of the most impactful examples of written propaganda in American history. In straightforward, compelling language, Paine argued for independence from Britain, dismantling the idea of monarchy and urging colonists to consider a republican form of government.

Paine’s pamphlet sold hundreds of thousands of copies, a staggering number given the smaller population and limited printing capabilities of the era. His direct style allowed the message to resonate across class lines—whether you were a shopkeeper, a farmer, or a member of the colonial elite, the emotional appeal of Paine’s words was hard to ignore. By vividly painting Britain as a tyrant exploiting the colonies for its own benefit, Paine provided a unifying rationale for why separation was not only justified but necessary.

Iconic Images and Symbols in Revolutionary Propaganda

While words carried tremendous weight, images also played a crucial role in conveying messages that could stir emotional reactions. Political cartoons, engravings, and symbols were a quick way to encapsulate complex ideas and rally colonists around shared sentiments.

“Join, or Die” Cartoon

Perhaps the most iconic image associated with the colonial period is Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” cartoon. First published in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1754, the cartoon depicted a segmented snake, each piece representing one of the colonies. Initially used to advocate for colonial unity during the French and Indian War, the image would later resurface as a rallying cry for cooperation against Britain. The symbolism was simple yet powerful: unity among the colonies was a matter of life or death. This easy-to-grasp message helped colonists from various regions see their fates as interconnected.

Paul Revere’s Engravings

Paul Revere, famous for his “Midnight Ride,” also left a notable mark through his engravings. One of his most famous works was an exaggerated depiction of the Boston Massacre (1770). Revere’s illustration, widely reprinted and circulated, showed armed British soldiers firing into an unarmed crowd of colonists, some of whom were depicted as helpless or fleeing. While elements of the image were inaccurate—such as portraying the colonists as entirely passive—it served its purpose in sparking outrage against the British military presence. By amplifying the sense of British aggression, it became a symbol of injustice that resonated with people who might never have set foot in Boston.

Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles

Beyond printed visuals, tangible symbols like Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles emerged as icons of defiance. Towns often designated a single tree as a place for posting messages or rallying. Colonists held meetings under these trees, sometimes even staging demonstrations. Liberty Poles—tall wooden structures erected in town squares—served a similar symbolic function. By raising a liberty pole, a community signaled its stance against British authority. These physical symbols became rallying points, making the revolutionary cause visible in everyday life. The emotional impact of seeing a liberty pole in your town square was often enough to spark curiosity or courage in neighbors.

Notable Voices: Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and Thomas Paine

A few key figures stand out for their mastery of propaganda during the American Revolution. They recognized that winning the hearts and minds of fellow colonists was just as crucial as any battlefield strategy.

Samuel Adams

Known as an agitator and a staunch critic of British policies, Samuel Adams was instrumental in organizing protests and shaping public opinion. He helped found the Sons of Liberty, a group committed to resisting the Stamp Act and other British measures. Adams recognized the power of words and played a pivotal role in drafting newspaper editorials and broadsides, carefully framing acts like the Boston Tea Party in ways that highlighted the colonists’ struggle for liberty rather than acts of vandalism. His persuasive rhetoric and networking skills helped knit together a grassroots coalition, turning local protests into larger, coordinated efforts.

Paul Revere

While Paul Revere is most famously remembered for his ride alerting the countryside of British troop movements, his contribution to revolutionary propaganda is also significant. Revere wasn’t just a messenger; he was a silversmith with a keen eye for craftsmanship, which he applied to engraving politically charged images. His depiction of the Boston Massacre exemplifies how one powerful image can fuel widespread indignation. Though the print was partially derived from another artist’s work, Revere’s version circulated so widely and quickly that it came to define how many colonists viewed the event.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was a game-changer. While many colonists had contemplated separation from Britain, Paine’s publication provided a unifying intellectual framework. He stripped away the complexities of monarchical rule, making a straightforward case for independence. His work was designed to be accessible, resonating with readers on an emotional and rational level. Paine also wrote a series of pamphlets known as The American Crisis, which kept morale high during the darkest days of the war. His opening line, “These are the times that try men’s souls,” became legendary and further emphasized how carefully chosen words could sustain a movement.

British Propaganda Efforts

It would be misleading to suggest that propaganda was solely the tool of the American colonists. The British government and loyalists in the colonies also deployed their own campaigns to sway public opinion. King George III’s ministers repeatedly issued statements declaring their authority and the necessity of taxing the colonies to defray costs of defense. Royal governors and loyalist printers published pamphlets and editorials urging colonists to remain loyal subjects of the Crown, warning of the economic and social chaos that could follow a full-scale rebellion.

Notably, some British propaganda painted the revolutionary leaders as radicals who endangered peace and stability. They highlighted instances of mob violence—such as tarring and feathering loyalists—to depict the revolutionaries as lawless troublemakers. The British government hoped that by portraying the rebellion as the work of a dangerous minority, they could dissuade moderate colonists from joining the cause. However, these messages often fell on deaf ears, particularly in areas where anti-British sentiment was already rampant.

Additionally, there were attempts at psychological warfare, with British commanders posting proclamations offering pardons to those who would lay down their arms. While these proclamations had limited success, they did stir some doubt among colonists who feared the consequences of outright rebellion. Nevertheless, the overwhelming momentum was on the side of the revolutionaries, whose more cohesive message of resisting tyranny struck a deep chord in colonial society.

The Impact of Propaganda on Public Sentiment

Propaganda helped transform the abstract idea of independence into a shared cause for many colonists. With literacy on the rise, pamphlets like Common Sense could quickly spread from hand to hand, often read aloud in taverns, churches, and town squares. This collective experience reinforced the sense of unity and urgency behind the revolutionary movement.

Beyond unifying colonists, propaganda fueled anger and resentment toward British authorities. For instance, sensational accounts of events like the Boston Massacre elevated tensions, making further escalation almost inevitable. When individuals read about or saw images depicting British troops as aggressors, they felt justified in their anger and more inclined to support extremist measures.

Moreover, propaganda had a cascading effect. Each protest or confrontation sparked fresh narratives—sometimes amplified or distorted—to reinforce the righteousness of the rebel cause. This cyclical pattern of action, reporting, and reaction accelerated the pace at which colonists moved from discontent to open rebellion. The widespread dissemination of these stories made it difficult for British officials to contain or downplay what was happening on the ground.

Propaganda’s Role in Mobilizing the Masses

Propaganda not only shaped opinions but also mobilized people to take tangible action. Whether through boycotts, military enlistment, or open protest, colonists felt emboldened by the belief that they were part of a larger movement destined to succeed. Publications such as newspapers and pamphlets often included calls to action, listing items to boycott or providing instructions for resistance. These directives were more likely to be followed because they were framed as part of a moral or patriotic duty.

Committees of Correspondence, organized in part by Samuel Adams, represented another layer of mobilization. These committees were tasked with spreading news, coordinating resistance, and monitoring British activities. They used letters, circulars, and even coded messages to keep colonies informed and aligned. This structured network was a testament to how well propaganda worked in keeping diverse groups united. Colonists from Georgia to New Hampshire could feel connected to the same overarching cause, even if they had never met each other.

Even religious figures sometimes joined the propaganda effort by framing the fight as a battle against tyranny blessed by God. Sermons that aligned biblical narratives with revolutionary ideals amplified the persuasive power of other forms of propaganda. Hearing a respected preacher describe the struggle in moral terms made it easier for congregants to view independence as not just politically correct but also divinely sanctioned.

The Aftermath and Legacy of Revolutionary Propaganda

When we look at the outcomes of the Revolutionary War, military campaigns and diplomatic efforts take center stage. However, the success of the American Revolution also owed much to the colonists’ ability to sustain public support and commitment over several years. Propaganda laid the ideological groundwork that kept people engaged, even when facing setbacks such as military defeats or harsh winters.

After the war, the traditions and techniques of revolutionary propaganda did not simply vanish. They laid the foundation for how the newly formed United States would communicate about politics and governance. Leaders understood the importance of shaping public opinion, and newspapers continued to be a powerful tool in American civic life. Early political parties used pamphlets and editorials to champion their platforms, while negative campaigns—often involving scathing caricatures—became staples of political discourse.

Additionally, the imagery and language from the revolutionary period endured, embedding itself into the national consciousness. The notion of Americans as people willing to stand up for liberty and resist tyranny became a core part of U.S. identity. This narrative, formed and reinforced by propaganda, influenced how Americans saw themselves and how they told their story to the world.

In education, many textbooks and historical accounts continued to emphasize the courage and unity of the colonists, sometimes glossing over internal conflicts or more controversial aspects of the Revolution. The continued influence of these narratives underscores just how powerful—and enduring—propaganda can be. Even in contemporary times, the myths and symbols born during the Revolution inform American political language and identity, from the slogan “Don’t Tread on Me” to the imagery of the Liberty Bell.

Conclusion

Propaganda was more than background noise in the American Revolution; it was a driving force that connected colonists across geographic and social divides, instilled a shared sense of injustice, and motivated them to action. From newspapers and pamphlets to dramatic engravings and stirring speeches, revolutionary propaganda harnessed emotions, ideas, and communal bonds to turn discontent into a cohesive push for independence. Leaders like Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and Thomas Paine recognized that winning the hearts and minds of everyday people was as pivotal to victory as any strategic military campaign.

This remarkable period set lasting precedents for how Americans—and people worldwide—would use messaging to promote political change. Today, the echoes of revolutionary propaganda can still be felt in the nation’s emphasis on freedom of speech, civic responsibility, and the capacity of popular movements to enact social and political transformations. By understanding the mechanisms, key players, and cultural context of propaganda in the American Revolution, students and enthusiasts of history can better appreciate not only how the United States came to be but also the enduring power of persuasive communication in shaping our world.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What role did propaganda play in the American Revolution?

Propaganda played a critical role in the American Revolution by shaping public opinion and fostering a sense of unity among the colonists. Through pamphlets, newspapers, and other forms of media, proponents of independence were able to communicate revolutionary ideas that emphasized the injustices of British rule and highlighted the benefits of self-governance. One of the most famous examples is Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” a pamphlet that laid out a compelling argument for independence and reached a wide audience. Propagandists used emotional appeals, persuasive language, and symbolic imagery to mobilize support for the revolution, spreading ideas of liberty, equality, and fraternity that resonated with a broad spectrum of colonial society. In contrast to modern interpretations of propaganda as inherently deceitful or misleading, the pro-revolutionary propaganda often presented their arguments sincerely, believing deeply in the cause they were advocating for. Ultimately, these efforts were instrumental in motivating colonists to fight for and achieve American independence.

2. How did colonial leaders use propaganda to unify the colonists?

Colonial leaders understood the power of a unified front and used propaganda to bring together the colonists from diverse backgrounds and with varied interests. Through the strategic use of language and media, they highlighted common grievances against British policies such as unfair taxation without representation, and the perceived tyranny of the British crown. Newspapers, pamphlets, and public speeches commonly featured stories of British oppression and colonial resilience, forging a shared identity among the colonists. Symbols like the Liberty Tree and slogans such as “Join, or Die” created visual and rhetorical cues that helped unify the different colonies under a single cause. Moreover, leaders like Samuel Adams, John Dickinson, and Benjamin Franklin were adept at using their writing skills to publish persuasive materials that underscored the necessity of collective action and mutual support. By setting a common ideological framework and emphasizing themes that resonated with different groups – including farmers, merchants, and intellectuals – colonial propaganda served as a powerful tool to cultivate solidarity and encourage revolutionary enthusiasm.

3. What tools and methods were most effective in American Revolution propaganda?

The American Revolution saw a variety of propaganda tools and methods employed to effectively influence public perception and galvanize the colonists. One key tool was the printed word, including pamphlets such as Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” and other writings that were disseminated widely among the colonist population. Newspapers played a vital role as well, with publications like the Boston Gazette and Pennsylvania Journal being at the forefront of Revolutionary propaganda efforts. These papers published essays, editorials, and letters that espoused the causes for independence and critiqued British policies. Broadsides, which were large single sheets of paper printed on one side, were commonly posted in public spaces to convey political messages quickly to a mass audience. Another highly effective method was the use of imagery; political cartoons and engravings, such as Paul Revere’s famous depiction of the Boston Massacre, leveraged powerful visuals to convey poignant political messages that could easily be understood by those who were illiterate. Public speeches and town meetings were also instrumental, as they allowed leaders to articulate revolutionary ideals in person and create a sense of immediacy and involvement among participants. Collectively, these tools and methods worked to build colonial consensus and mobilize support for the revolutionary cause.

4. How did Loyalists respond to the revolutionary propaganda?

Loyalists, who remained supportive of the British Crown, responded to revolutionary propaganda with publications of their own, attempting to counter the arguments put forth by the Patriots. These Loyalist writers and printers produced pamphlets, essays, and newspapers that defended British policy, loyalty to the king, and the benefits of staying under British rule. Many Loyalists argued that the rebellion against the Crown was unjust and could lead to unnecessary chaos and suffering. They sought to cast doubt on the motives of revolutionary leaders, often claiming that these figures were instigators of disorder or seeking personal gain. However, the Loyalists faced considerable challenges, as their perspectives were often outnumbered and overshadowed in the colonies by the prolific production and distribution of Patriot propaganda. In some areas, Loyalists were even subject to social ostracism and hostility, making it difficult for their counter-propaganda efforts to gain much traction. Nevertheless, Loyalist propaganda did find a receptive audience in certain regions and social strata, such as among colonial officials, landowners with strong commercial ties to Britain, and those who feared the economic or societal upheaval that independence might bring.

5. How did propaganda influence international perceptions of the American Revolution?

The use of propaganda in the American Revolution not only aimed to influence colonial and British audiences but also played a crucial role in shaping international perceptions, particularly in securing foreign support. The American Revolutionaries understood the importance of international recognition and assistance, especially from France, which played a decisive role in the eventual success of the Revolution. Revolutionary leaders and propagandists highlighted themes of liberty and resistance to tyranny, framing the American struggle as part of a broader, universal fight for rights and freedoms. Diplomats like Benjamin Franklin were adept at using American propaganda to influence foreign public opinion, portraying the Revolution as a commendable pursuit of independence by an oppressed people. These efforts helped to establish sympathy for the American cause and communicate the legitimacy of their movement to foreign powers. Such propaganda efforts were key in winning the support of the French government, who were enemies of Britain and saw the American Revolution as an opportunity to weaken British power globally. Ultimately, the interplay of propaganda on both sides of the Atlantic contributed significantly to securing the eventual alliances that were vital for the colonial struggle against Britain, helping to transform a colonial insurrection into a credible international cause.