The Underground Railroad stands as one of the most courageous examples of collective action in American history. Built on secrecy and daring, this network of routes and safe houses gave freedom-seeking enslaved people a fighting chance to escape the brutality of bondage. But it wasn’t just an escape route: it was a powerful symbol of defiance that awakened the nation’s conscience, influenced federal law, and helped ignite the events leading to the Civil War. Understanding the Underground Railroad’s creation, operation, and impact offers valuable lessons about the power of collaboration, resilience, and moral conviction—lessons that still resonate today.

Early Origins and the Drive to Resist Slavery

Enslaved people in America had been attempting to break free of captivity since the earliest days of colonial settlement. Acts of resistance, both small and large, were constant reminders that no human being would accept being deprived of freedom without protest. Over time, these efforts to escape became more organized and sophisticated.

By the late 18th century, several religious and social groups, notably the Quakers, had openly taken a stance against enslavement. Quakers believed in the inherent value of every human being—regardless of skin color—and felt duty-bound to help those who were being oppressed. In areas like Pennsylvania, which already had a significant Quaker population, local communities quietly worked together to help self-emancipated individuals find safer territory in the North, and sometimes Canada, where slavery had been outlawed.

These early cooperative efforts laid the foundation for what would become known as the Underground Railroad. Despite what the name suggests, it wasn’t an actual railroad nor was it literally underground. Instead, it was a secret network—routes crisscrossing states, with “stations” being the homes, churches, or barns of sympathetic abolitionists who sheltered those in flight. People involved used railroad terminology as code: “conductors” guided freedom seekers, and “passengers” referred to the enslaved individuals on the run. This coded language helped avoid detection by slave catchers and law enforcement officials sympathetic to slaveholders.

Growing Tensions and Legislative Challenges

The Underground Railroad became even more active as tensions between the North and South intensified. Northern states, with their growing abolitionist sentiment, often offered some level of protection or acceptance to those who managed to escape. Meanwhile, Southern states saw the steady trickle of escapees northward as a serious economic and social threat. To address that threat, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, giving slaveholders and their agents more freedom to recapture enslaved individuals who had fled.

But even that legislation didn’t stem the tide of escape attempts. Enslaved people, determined to be free, risked their lives to flee, and sympathetic Northerners defied legal consequences to help. Southern lawmakers responded by pushing for stronger federal legislation. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 imposed heavy penalties on anyone assisting an escapee, compelling citizens to participate in the recapture of freedom seekers. For conductors on the Underground Railroad, this heightened the risk significantly. Yet, instead of shutting down the network, the new law spurred many abolitionists to intensify their efforts. Their moral convictions overshadowed their fear of legal repercussions and further fueled the Underground Railroad’s expansion.

Key Figures and Heroes

No discussion of the Underground Railroad is complete without highlighting the individuals who risked everything to keep it running. While countless brave men and women contributed, certain figures stand out for their extraordinary efforts:

Harriet Tubman: Affectionately known as “Moses” to those she guided, Harriet Tubman escaped slavery herself in 1849. Not content with her own freedom, she returned to the South multiple times to guide her family and many others to freedom. Tubman’s intelligence, faith, and unyielding courage—despite bounties placed on her head—turned her into the face of the Underground Railroad. Her success inspired many and showcased what one determined individual could achieve.

Frederick Douglass: Though more widely known as an orator, writer, and public abolitionist, Frederick Douglass played a crucial background role in the Underground Railroad by opening his Rochester, New York home to those traveling north. Douglass’s personal story of escaping slavery, combined with his eloquence, made him a leading voice against the institution of slavery. He provided both practical assistance to individuals seeking freedom and intellectual ammunition for the growing abolitionist movement.

Levi Coffin: Nicknamed the “President of the Underground Railroad,” Levi Coffin was a white Quaker who dedicated much of his life to aiding freedom seekers. He and his wife, Catharine, opened their Indiana and later Ohio homes to thousands of individuals fleeing slavery. The Coffin household became so well-known among conductors and passengers that it was almost a required stop on the route north.

William Still: Often called the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” William Still documented detailed accounts of those he helped, creating what is now an invaluable historical record. Still was also involved in the Vigilance Committee, an organization that coordinated escape plans and defended runaways in court.

These heroes formed a network whose purpose extended beyond just helping people run from bondage. They shared inspiring stories, arranged resources, and laid the groundwork for anti-slavery sentiment to flourish throughout the North. Their unwavering stance sent a clear message to slave owners: The quest for freedom wasn’t a crime, but rather a moral and human right that could not be lawfully or ethically suppressed.

Daily Realities and Secrets of the Network

The Underground Railroad was a constantly shifting operation. Safe houses changed frequently; routes were modified to evade capture. People on the run often traveled under cover of night, guided by the North Star—another reason nighttime journeys were commonly referred to as “following the Drinking Gourd.” Conductors used secret knocks, codes, and signals to identify one another and to recognize whether a house was safe to enter.

Communication was generally spread through word of mouth, and newspapers sympathetic to the cause occasionally slipped in coded messages. For African American “stationmasters,” offering refuge was particularly perilous because they were already targets of discrimination. A free Black person caught assisting escapees might be sold into slavery themselves or face severe, life-threatening punishment.

Despite these dangers, the individuals involved persisted—fueled by faith, ideology, and empathy. Their dedication to the cause spoke volumes, reinforcing the idea that slavery, as a system, was neither universally accepted nor morally defensible. By demonstrating that a growing segment of American citizens were willing to defy the law and risk their safety to help enslaved people, the Underground Railroad exposed the moral fault lines in a country that championed liberty but also tolerated human bondage.

Catalyzing Social and Political Change

The existence and success of the Underground Railroad didn’t singlehandedly end slavery, but its influence was undeniable. The steady flow of escapees north put a spotlight on the inherent instability and cruelty of slavery. Every daring escape publicized in abolitionist newspapers chipped away at the narrative that enslaved people were content or “needed” slavery for their own good. It became harder for slaveholders to argue that enslaved individuals were happy or better off under their masters’ control.

Moreover, the public debate about the Underground Railroad gave abolitionists a powerful platform. Stories of harrowing journeys and families torn apart placed empathy at the forefront of the national conversation. These firsthand accounts stirred compassion, outrage, and a push for stronger anti-slavery legislation in Northern states.

The Railroad also highlighted fundamental flaws in federal laws designed to protect slaveholders’ interests. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, for example, forced many moderates in the North—people who may not have identified as staunch abolitionists—to confront the brutality of slavery. Watching neighbors or friends get prosecuted simply for giving a hungry, terrified traveler food or shelter compelled everyday citizens to question the morality of the law. In this way, the Underground Railroad helped propel the issue of slavery from a regional concern to a contentious national debate. The moral, legal, and human-rights implications laid the groundwork for the political battles that led to the Civil War.

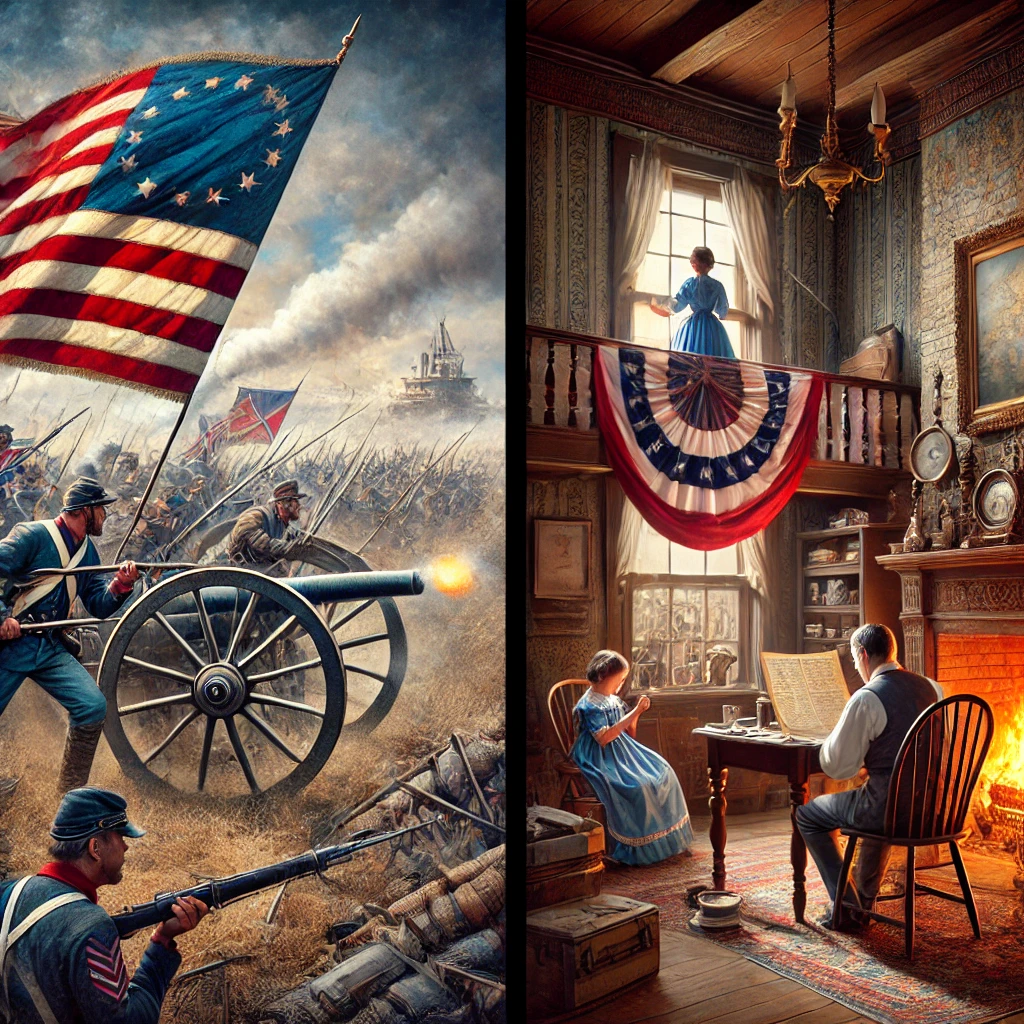

Impact on the March Toward Civil War

From the early 1800s to the mid-century, debates around slavery had become increasingly volatile. As new states joined the Union, questions about whether they would permit or ban slavery sparked intense confrontations in Congress. Compromises like the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 served as temporary fixes, but each new law only widened the ideological gap between pro- and anti-slavery factions.

The Underground Railroad, in operation against these shifting legal and political backdrops, was more than a means of escape. It was a catalyst that exposed the moral contradictions in American life. Even some Northerners who were previously ambivalent became uncomfortable with the idea of participating in slave-catching duties. Meanwhile, Southern planters seethed over what they viewed as the North’s refusal to honor federal laws and property rights. The presence of a widespread network openly defying the law fueled resentment and paranoia in the South, contributing to the tension that would soon erupt into violence.

In many ways, the Underground Railroad’s success in aiding thousands to escape was a direct, visible challenge to the South’s economic and social structures. The fear that slaveholding states could lose large numbers of enslaved people, or that Northern states would continue to defy federal law, played a major role in secessionist sentiment. Southern leaders became convinced that their “way of life” was under imminent threat, and this anxiety helped pave the way for the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What was the Underground Railroad and how did it operate?

The Underground Railroad wasn’t a railroad in the literal sense but rather a vast network of secret routes and safe houses that extended from the southern United States to the northern states and even into Canada. Operated by a coalition of free Black people, antislavery activists, and sympathizers from various walks of life, its primary purpose was to assist enslaved African Americans in escaping to freedom. Those involved were known as “conductors,” while the escapees were referred to as “passengers.” Safe houses were “stations,” and their proprietors were “stationmasters.” Communication and coordination were clandestine and relied heavily on coded language and signals to evade capture by slave catchers and law enforcement sympathetic to slaveholding interests.

2. How did it influence the abolition movement and the eventual end of slavery?

The Underground Railroad was more than just a means of escape – it became a potent emblem of resistance against the institution of slavery. Its success challenged the complacency and moral apathy of the broader American public, highlighting the cruel realities of slavery in stark terms. The visibility of the network and the stories of extraordinary courage and resilience it produced helped to galvanize the abolitionist movement by humanizing the plight of the enslaved and presenting their quest for freedom as a legitimate and urgent cause. Moreover, the large number of successful escapes emboldened abolitionists, fueling Northern sympathy and creating political pressure that helped to shape public policy. The heightened awareness and advocacy hastened legislative debates and actions leading to the abolition of slavery, culminating in the Civil War and the adoption of the 13th Amendment.

3. Who were some notable figures involved in the Underground Railroad?

Several key figures left indelible marks on the history of the Underground Railroad. Harriet Tubman, often called “Moses,” was renowned for her bravery and tactical genius, personally leading numerous missions into the South to rescue over 70 enslaved people. Frederick Douglass, himself a former enslaved person, became a powerful voice in the abolitionist movement, providing both strategic insight and sheltered passage for freedom seekers. William Still, known as the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” meticulously documented the stories of those he aided, offering invaluable testimony to the scale and impact of the Railroad. Additionally, figures like Levi Coffin, often called the “President of the Underground Railroad,” and John Rankin provided critical support through their extensive networks of safe houses.

4. How did the United States government respond to the Underground Railroad?

The existence and operation of the Underground Railroad provoked significant tension between Northern and Southern states. In response, the Federal Government enacted laws to appease Southern slaveholders and curtail abolitionist activities. The most infamous of these was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which mandated that escaped enslaved people be returned to their owners and imposed hefty penalties on anyone aiding in their escape. However, rather than quelling the spirit of the Railroad, this legislation often had the opposite effect, intensifying the resolve of abolitionists and sparking widespread Northern outrage. It also bolstered support for the Underground Railroad as more people realized the law’s moral injustices, accruing sympathy and active participation in defiance of federal edicts.

5. How did the Underground Railroad contribute to the start of the Civil War?

The Underground Railroad played a vital role in sowing the seeds of conflict that erupted into the Civil War. By facilitating the escape of thousands of enslaved individuals, it starkly demonstrated both the widespread discontent with slavery and the lengths people were willing to go to help others claim freedom. The visible success and defiance of the Railroad exacerbated sectional tensions, provoking political and economic concerns related to the loss of “property” (enslaved people) and challenging Southern power structures. The moral outrage and activism it generated contributed to the polarization of the nation, laying bare the irreconcilable differences between free and slave states. As the Railroad continued its clandestine operations, it deepened the schism that would lead to the secession of Southern states and the eventual outbreak of the Civil War.