The 1920s was a decade of dramatic change and social upheaval in the United States, often referred to as the Roaring Twenties. It was a time of economic growth, cultural transformation, and significant social tensions—particularly around issues of race, immigration, and morality. One of the most notable and alarming developments during this period was the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). While the original Klan was born in the aftermath of the Civil War, its second incarnation emerged with renewed force in the early 20th century, leaving a lasting impact on American society.

In this article, we will examine how this second Klan gained traction in the 1920s. We will explore the social, economic, and political factors that contributed to its rapid growth, as well as the deep anxieties and cultural shifts that made its hateful rhetoric resonate with segments of the American public. We will also look at how the Klan influenced local and national politics, shaped public debates on topics like immigration and morality, and clashed with a variety of opponents who fought to uphold civil rights and social justice.

By reviewing this dark chapter of American history, we can gain insights into the complexities of the Roaring Twenties—an era known for flappers, jazz, and booming business, but also for rising racial violence and nativist sentiments. Understanding the Klan’s influence during the 1920s is crucial for recognizing how extremist ideologies can take root in times of social tension. Ultimately, this knowledge reminds us of the importance of safeguarding democracy, civil liberties, and equality for all citizens.

Roots of Resurgence

The Ku Klux Klan first emerged in the post-Civil War South as a vigilante group determined to maintain white supremacy and oppose the newly gained civil rights of African Americans. By the late 19th century, federal crackdowns had significantly weakened the organization. Yet, in 1915, the Klan was reestablished by William Joseph Simmons at Stone Mountain, Georgia. This new Klan drew inspiration from popular culture—most notably the film The Birth of a Nation by D.W. Griffith, which glorified the Klan’s original incarnation. Simmons capitalized on growing national sentiment that romanticized the organization’s past, positioning the group as defenders of traditional American values.

But the film alone did not account for the Klan’s dramatic rise in the 1920s. World War I had just ended, and America was grappling with rapid social changes. The Great Migration saw hundreds of thousands of African Americans moving North in search of better opportunities, triggering racial tensions in new regions of the country. Meanwhile, there was a surge in immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, fueling nativist fears about cultural and ethnic change. The postwar period also saw the first Red Scare, with widespread anxiety over communism. These overlapping concerns—race, immigration, and political ideology—gave the Klan an appealing platform for those who felt threatened by a changing America.

Additionally, Prohibition, which went into effect in 1920, introduced further social and moral battles that the Klan exploited. They presented themselves as enforcers of moral righteousness, claiming to stand against the evils of alcohol, vice, and corruption. This stance, coupled with their message of “100% Americanism,” resonated with people across various regions. The Klan was no longer just a Southern phenomenon; it found supporters in the Midwest, the Southwest, and even parts of the Northeast. Recruiters traveled the country, stoking fears of minority groups and immigrants, while promising moral reform and societal order.

The group’s second-wave success also hinged on savvy organizational and marketing tactics. The Klan employed a modern membership drive approach, using professional publicists like Edward Young Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler. Their skillful campaigns used mass advertising, recruitment rallies, and stirring speeches to amplify the Klan’s visibility. This wave of publicity made joining the KKK feel not only acceptable but almost fashionable for those inclined to support nativist and racist ideologies. This toxic combination of national fear, nostalgia for an imagined “simpler time,” and professional propaganda laid the groundwork for the Klan’s astounding growth in the 1920s.

Membership and Structure

A major difference between the Klan of the 1920s and its earlier iteration was its extensive, hierarchical organizational structure. No longer a loosely knit vigilante group, the second Klan was organized like a fraternal society with clearly defined leadership levels. From the Imperial Wizard at the top to state-level Grand Dragons and local Klaverns, each level had designated responsibilities and rituals designed to foster a sense of unity and belonging among members.

By the mid-1920s, estimates of KKK membership ranged anywhere from three to five million individuals, though the exact numbers are difficult to verify. What is clear is that this was not a fringe movement lurking only in rural backwaters—it had significant reach in urban areas and among various demographics. Members included small-business owners, farmers, professionals, and even local politicians who saw membership as a way to garner support and social connections. Prospective members found the promise of camaraderie and a shared identity appealing. The notion of joining a “patriotic” fraternity that protected traditional values, upheld Prohibition, and guarded against perceived moral threats was enticing to many.

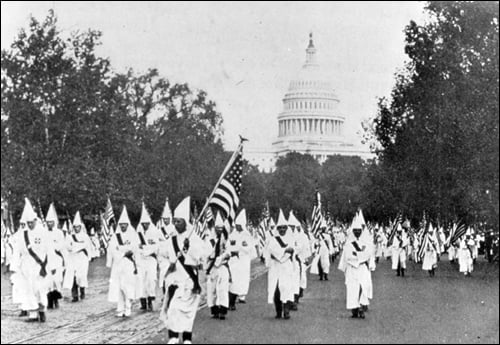

To maintain loyalty and camaraderie, the Klan held elaborate rituals, parades, and cross-burning ceremonies. While these displays had their roots in violent intimidation, they were also choreographed events meant to solidify group identity. Klansmen wore their distinctive white robes and hoods, marched in torchlit processions, and used fiery crosses to represent their supposed religious mission. Though these displays were intimidating—particularly to minority communities—they also served as public spectacles that attracted attention and gave members a sense of unity and power.

Moreover, the Klan financed itself largely through membership dues and the sale of Klan-branded goods: robes, hoods, and other paraphernalia. This allowed the organization’s leaders to profit handsomely. The emphasis on recruitment was therefore not just ideological but also financial. The more members brought into the fold, the more money flowed upward through the ranks. This businesslike model helped sustain the Klan during its most active years, even as newspapers and civic leaders occasionally condemned their activities.

Ideology and Tactics

At its core, the Klan’s ideology in the 1920s centered on white supremacy, Protestant nativism, and the enforcement of a conservative moral code. Klan members believed that Catholics, Jews, African Americans, immigrants, and other minority groups posed a threat to the “purity” and stability of America. This bigotry often aligned with a broader national climate of xenophobia, eugenics-based thinking, and racist pseudoscience. The Klan used fearmongering, scapegoating, and relentless propaganda to cast itself as the defender of real Americans against these “outsider” groups.

The Klan’s tactics were not limited to intimidation and violence, although cross burnings, beatings, and lynchings were among the most horrendous ways they terrorized Black Americans and other targeted populations. In many communities, the Klan exercised influence through economic pressure, boycotting businesses owned by or friendly to minority groups, and sometimes even pressuring employers to fire people who did not fit their vision of America. They also spread rumors and used smear campaigns against political or social adversaries.

Furthermore, the Klan took advantage of religious sentiments to justify its beliefs. Claiming to uphold Protestant Christian values, members often argued that they were fighting against moral decay. They targeted groups they perceived as immoral or “un-American,” including not just racial and religious minorities, but also people who engaged in activities like drinking alcohol or breaking Prohibition laws. This moralistic stance enabled the Klan to recruit among churchgoers who saw them as an extension of their religious convictions.

All the while, the Klan’s national leadership attempted to cloak their racism in patriotic language. They spoke about “100% Americanism” and the need to safeguard the nation’s founding principles. These claims resonated with individuals worried about communism, secularism, and the rapidly changing face of American demographics. Underneath this veneer of patriotism, however, the driving force behind KKK ideology was, undeniably, a relentless focus on preserving white Protestant dominance in all aspects of public and private life.

Political and Social Influence

During the early to mid-1920s, the Klan’s influence extended well beyond isolated marches and private ceremonies. Members sought positions of power in local, state, and even national politics. Across the country, Klan-backed candidates ran for offices ranging from school board seats to governorships. In some areas, the Klan’s backing virtually guaranteed victory due to the sheer number of local members and supporters. Consequently, the Klan’s interests began to shape policies at various levels of government.

In states like Indiana, Colorado, and Oregon, the Klan had significant political sway. Indiana’s Grand Dragon, D.C. Stephenson, became one of the most powerful men in the state, orchestrating elections and influencing legislation. Politicians who wished to remain in favor sometimes felt pressured to adopt or at least tolerate the Klan’s views on immigration, education, and religious minorities. Some public schools were influenced by Klan ideas, discouraging the teaching of evolution or promoting a narrow Protestant curriculum.

The Klan also engaged in community outreach to solidify its influence. Members sponsored charity events, held picnics, and organized parades to present themselves as patriotic neighbors dedicated to civic improvement. While these events might seem benign, they served to normalize the Klan’s presence and lend legitimacy to its discriminatory ideology. When the community saw Klansmen engaging in public service, it became easier for some to overlook or excuse the organization’s more nefarious actions.

Despite the Klan’s attempts to appear respectable, their activities met with significant backlash. Newspapers sometimes uncovered scandals involving Klan leaders, detailing the corruption, violence, and hypocrisy behind the group’s patriotic façade. Yet for a time, these revelations did little to dampen the Klan’s allure. Their hold was strong enough in some regions that they effectively directed law enforcement, judicial decisions, and public policy. This widespread reach demonstrated just how deeply embedded the group had become in American life during the 1920s—and how many Americans were willing to turn a blind eye to its overt racism and violence if it aligned with their own fears and biases.

Influence on Culture and Media

While we often think of culture in the 1920s as being defined by jazz, the Harlem Renaissance, and a break from traditional norms, it’s important to remember that cultural narratives can differ greatly depending on one’s viewpoint. The Klan was adept at using the media of the day to propagate its message. Klan newspapers and magazines championed their cause, publishing stories that vilified minorities and celebrated Klan-related achievements. They also spread conspiracy theories regarding Catholics, Jews, and other groups, fueling paranoia among the receptive public.

Furthermore, Klan-affiliated writers and speakers participated in broader public debates. They organized rallies not just as intimidation tactics but also as community events. These gatherings often featured speeches that blurred the lines between patriotism and prejudice, reinforcing the group’s image as defenders of American traditions. Such rallies attracted both curious onlookers and genuine supporters, creating a sense of spectacle and fascination around the Klan.

Parallel to these efforts, there was a counter-narrative led by African American newspapers such as the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, which worked to expose Klan atrocities and empower Black communities. Civil rights leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois also published works that warned against the Klan’s influence and encouraged activism and legal defense. This tug-of-war in the media landscape underscored the cultural divide of the era. On one side, you had the Klan pushing for an exclusionary version of “Americanism,” and on the other, you had minorities, activists, and allies championing a broader, more inclusive vision of the nation.

By the late 1920s, the Klan’s own internal strife began to reach the public eye, and investigative journalists became bolder in exposing leadership scandals and financial malfeasance. Sensational stories about corruption at the top of the organization chipped away at its façade of moral purity. Still, the cultural impact of the Klan’s messaging lingered, reflecting the pervasive biases and anxieties harbored by many white Americans in that era.

Resistance and Opposition

While the Ku Klux Klan gained a concerning amount of influence during the 1920s, it faced vigorous opposition from various corners of American society. African American communities were at the forefront, often forming self-defense groups or turning to organizations such as the NAACP for legal support. Leaders like James Weldon Johnson and Walter White used lawsuits and public awareness campaigns to challenge discriminatory practices and protect Black citizens from Klan violence.

Religious minorities, including Catholics and Jews, organized to counter Klan intimidation. Knights of Columbus councils became more active in speaking out against anti-Catholic rhetoric, while Jewish civic groups published bulletins and funded newspaper articles exposing Klan falsehoods. These acts of resistance were crucial in preventing the Klan from monopolizing the public discourse on morality and national identity.

Local communities sometimes rose up in collective defiance. In places like Oklahoma, farmers and laborers formed alliances to fight back against Klan-backed politicians, fearing that racial and religious discrimination would undermine workers’ rights. Newspapers played a pivotal role in this opposition, with many mainstream publications eventually recognizing the need to report on Klan violence more openly. Journalists like Grover Cleveland Hall of the Montgomery Advertiser in Alabama criticized the Klan’s tactics and leaders, winning a Pulitzer Prize for their efforts to shine a light on racial terrorism.

Over time, these acts of resistance began to weaken the Klan’s grip. Public protests, legal battles, and investigative reporting forced Americans to confront the brutality behind the hoods and robes. While the Klan attempted to stifle dissent through intimidation, its opponents remained undeterred. By the late 1920s, shifting political climates and grassroots activism contributed to the Klan’s decline, though it would take years—and continued civil rights struggles—to mitigate the damage done by this era of heightened racist and nativist fervor.

Internal Strife and Decline

Ultimately, the Klan of the 1920s was undone as much by its own internal failings as by external opposition. Corruption within the leadership ranks became increasingly apparent, with some top figures accused of embezzlement, fraud, and abuse of power. One of the most infamous scandals involved Indiana Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson, who was convicted of second-degree murder in 1925. Stephenson’s trial revealed the brazen corruption and violence at the highest levels of the Klan, discrediting the organization in the eyes of many former supporters.

Additionally, the public began to lose trust in the Klan’s self-proclaimed moral authority. As newspapers published exposés on lavish spending by Klan leaders, many rank-and-file members realized their dues were lining the pockets of a select few rather than funding community improvements or patriotic causes. The Klan’s promises of religious and civic reform were tarnished by evidence of personal enrichment and scandalous behavior.

On top of that, the social and political landscape began to shift. The roaring economy of the mid-1920s started to cool down by the end of the decade, culminating in the Great Depression of the 1930s. With new economic hardships came new priorities. Many Americans, struggling to make ends meet, lost interest in sustaining an organization that thrived on scapegoating others instead of offering real solutions to widespread poverty and unemployment.

Finally, the force of public opposition took its toll. Court cases, anti-Klan laws, and lawsuits limited the Klan’s ability to operate openly. Activists pressed for investigations into local officials suspected of collusion, making Klan members less eager to wear their hoods in public. By the early 1930s, the Klan had lost much of its mainstream support. While vestiges of the group remained—and would resurface later in the 20th century—the mass movement of the 1920s was effectively over.

Legacy and Lessons

The rise and fall of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s offer important lessons about how hate groups can capitalize on social anxiety and cultural shifts to achieve mainstream acceptance. The Klan tapped into economic fears, racial prejudices, religious tensions, and concerns about morality to recruit millions of Americans to its cause. By using modern marketing techniques, aligning with political figures, and positioning itself as a defender of traditional values, the Klan was able to wield influence far beyond what many would have thought possible.

While the Klan did eventually implode due to internal corruption and external pushback, the scars left by its campaigns of intimidation and violence persisted for decades. Communities of color, religious minorities, and immigrants bore the brunt of the Klan’s wrath, often with devastating and long-lasting consequences. The Klan’s example underscores the dangerous power of fear-based rhetoric, and the ease with which it can spread when individuals feel threatened by societal change.

Yet, the 1920s also demonstrate that robust opposition movements—driven by courageous journalism, community organization, and legal action—can help expose and combat hateful ideologies. Anti-Klan efforts laid an early foundation for the broader civil rights battles that would come later in the century. By revealing the Klan’s corruption and challenging its violent activities, determined activists and everyday citizens helped remove the cloak of legitimacy the Klan tried to drape over itself.

Today, the history of the Klan’s rise in the 1920s still resonates. Times of upheaval can give way to extremist movements, even in societies that consider themselves modern and democratic. Remaining vigilant against racism, nativism, and religious intolerance is essential to upholding a pluralistic and equitable nation. Studying this era reminds us that hate flourishes in the shadows of ignorance and fear, and that informed, active communities are the most effective means of ensuring that such movements do not gain a foothold.

Conclusion

The story of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s is a stark reminder that prejudice and hatred can gain momentum when societal conditions are ripe and people are searching for clear answers to complex problems. Instead of finding constructive solutions, many in that era were drawn to the Klan’s promise of swift “justice” and moral reform—even as it terrorized minority populations and perpetuated systemic racism. The Klan’s tactics and rhetoric capitalized on widespread anxieties about race, religion, immigration, and shifting cultural norms, ultimately allowing it to secure an unsettling amount of power.

At the same time, the Klan’s meteoric rise was not uncontested. Legal challenges, courageous journalists, and diverse communities joined forces to expose the group’s corruption, dismantle its leadership, and refute its hateful ideology. Their work serves as a beacon for how organized, principled resistance can curb the spread of destructive movements. The legacy of that battle continues to inform modern efforts to fight extremism, racism, and bigotry in all their forms.

By understanding the Klan’s resurgence in the 1920s—how it developed, who it appealed to, and the strategies it employed—we gain valuable perspective on how hate groups can exploit social rifts to gain acceptance. More importantly, we learn about the power of collective action in defending democratic ideals and civil liberties. Even in an era characterized by booming business, new cultural freedoms, and technological advancements, the Klan’s rise stands as a sobering lesson. The fight to maintain inclusivity and justice is ongoing, and remembering history can guide us toward building a society where the values of equality, freedom, and respect for human rights prevail.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why did the Ku Klux Klan experience a resurgence in the 1920s?

The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s was primarily fueled by a mixture of social, economic, and cultural factors prevalent during the era. The decade was marked by significant immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to urban centers in the North. These demographic shifts led to heightened racial and ethnic tensions among white Americans who feared losing their social and economic status. The Klan capitalized on these fears, promoting itself as a defender of traditional American values and white Protestant supremacy.

The post-World War I period saw many veterans returning to a changed nation, where the economic prosperity of the Roaring Twenties was not evenly distributed, leading to widespread anxiety. The economic instability paired with cultural changes, such as the rise of the ‘flapper’ culture and the Prohibition era, fueled a backlash against what many perceived as moral decline. The Klan exploited these societal fears by portraying themselves as purveyors of morality and law and order, focusing their recruitment on this narrative.

Additionally, the Klan’s expansion was facilitated by modern marketing strategies. They effectively used mass media of the time, like newspapers and pamphlets, to spread their ideology. The organization’s adoption of corporate-style hierarchy and aggressive membership drives allowed them to expand rapidly. Skillful rhetoric and rallying of collective fears gave the Klan a platform, and by promoting an ‘us versus them’ mentality, they grew to encompass a wide range of bigotries, targeting not just African Americans, but also immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and anyone perceived as different. All these factors coalesced to help the Klan reemerge as a formidable, albeit horrific, force in American society during the 1920s.

2. What was the impact of the Ku Klux Klan’s growth on American society in the 1920s?

The impact of the Ku Klux Klan’s growth during the 1920s on American society was profound and far-reaching, influencing social, political, and cultural landscapes. The Klan’s rapid expansion during this period allowed it to infiltrate various layers of society, including politics, law enforcement, and even education, thereby embedding its ideology more deeply than in previous iterations.

Socially, the Klan propagated a culture of fear and division, particularly in communities where racial, ethnic, and religious diversity was on the rise. They often resorted to intimidation tactics, including public lynchings, beatings, and acts of arson against minority communities and any individuals they considered subversive or outside their vision of ‘traditional’ America. These acts of terror were aimed at suppressing the rights and freedoms of these communities, which consequently sowed fear and hostility, reinforcing segregated and polarized societies.

Politically, the Klan wielded considerable influence by getting members and sympathizers elected into local and state offices across the country. Their significant political clout enabled them to push legislation that aligned with their beliefs, such as immigration restrictions and anti-miscegenation laws. This political power underscored their ability to affect change on a legislative level, further institutionalizing their prejudiced agendas.

Culturally, the presence and actions of the Klan incited a backlash from civil rights groups and progressive movements, galvanizing African Americans and other minority groups to organize and advocate for their rights. This era also saw the rise of influential figures who challenged the Klan’s narrative, contributing to the slow but steady progress toward civil rights.

The Klan’s resurgence during the 1920s left a legacy of division and tension that persisted long after their influence waned. The period highlights an era in which fear and hate found fertile ground, impacting generations and emphasizing the importance of vigilance against such ideologies.

3. How did the Ku Klux Klan sustain its mass membership and widespread influence during the 1920s?

The Ku Klux Klan sustained its mass membership and widespread influence during the 1920s through a variety of strategic approaches that capitalized on the era’s anxieties and communication advancements. At its height, the organization claimed millions of members across the United States, transcending its Southern origins and becoming a national movement largely due to its sophisticated organizational and recruitment strategies.

One of the key methods for maintaining and growing its membership was through savvy marketing and modern public relations techniques. The Klan used newspapers, leaflets, and mail-order campaigns to disseminate their message and recruit new members. They organized elaborate ceremonies, parades, and rallies designed to create a sense of belonging and grandeur, making membership appeal both a social and patriotic duty for many.

The Klan also exploited the power of word-of-mouth and local networks. By positioning itself as a fraternal organization and presenting tangible benefits to potential members, such as networking opportunities, business connections, and a shared sense of belonging, it attracted individuals across different economic backgrounds. The Klan’s emphasis on community and family values further entrenched it in local societies.

To maintain influence, the Klan focused on embedding its members into key societal positions, particularly in law enforcement, politics, and education. This infiltration allowed them to enforce their ideologies through legislative and social pressures. They lobbied for and facilitated laws that aligned with their nativist and segregationist beliefs, further solidifying their impact on national policies.

By tapping into the inherent fears of social change, the Klan managed to sustain its membership until external pressures, such as governmental scrutiny and financial mismanagement, led to its eventual decline. Their sophisticated approach to recruitment and influence in the 1920s remains a chilling reminder of how fearmongering and prejudice can be institutionalized when left unchecked.

4. What role did media and propaganda play in the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s?

Media and propaganda played a pivotal role in the rise and expansion of the Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s, serving as essential tools for disseminating their ideology and recruiting members. This period saw the Klan use cutting-edge communication strategies to amplify its message and attract a national audience.

The Klan published its own newspapers and periodicals dedicated to promoting its views and counteracting any negative portrayals in the mainstream media. Publications such as “The Fiery Cross” and “The Kourier” offered narratives that championed white supremacy, American nativism, and xenophobia. These outlets provided a curated message that reinforced the Klan’s image as a moral arbiter and defender of traditional American values.

Beyond print media, the Klan harnessed the power of symbolism and spectacle to propagate its message. Iconic imagery such as the burning cross became a widely recognized tool of intimidation, serving both as a literal call to arms and a symbol of their fiery passion for their cause. The grandiosity of Klan rallies, often featuring parades, speeches, and demonstrations, served to galvanize current members and attract new recruits. These events were often covered by the press, further increasing the Klan’s visibility.

The Klan’s adept use of radio broadcasts, a new technology in the 1920s, also allowed them to reach a broader audience than ever before. By embracing media innovations, the Klan adapted to the cultural landscapes of the Roaring Twenties, transforming from an exclusively localized terror organization into a broad political movement.

However, the same media that the Klan exploited eventually played a significant role in its decline. Investigative journalism exposed the corruption and criminal activities of the Klan’s leadership, undermining its moral legitimacy. Critically, organizations and activists began using publications and public platforms to counteract the Klan’s propaganda, ultimately helping to diminish its power and disband its chapters.

5. What were the key factors that led to the decline of the Ku Klux Klan by the late 1920s?

Several key factors contributed to the decline of the Ku Klux Klan by the late 1920s, marking the end of its brief but powerful resurgence. Though it reached the peak of its influence earlier in the decade, the organization faltered due to internal and external pressures that weakened its structure and chipped away at its credibility.

One of the primary internal factors was the rampant corruption and financial mismanagement within the organization. The Klan’s leadership, including prominent figure David C. Stephenson, was embroiled in numerous scandals that revealed significant moral and fiscal corruption. Stephenson’s conviction for the rape and murder of a young woman was particularly damning and sparked widespread disillusionment among members and the public, shattering the Klan’s self-styled image as a moral and family-centric organization.

In addition, the Klan faced increasing legal and governmental scrutiny. Both state and federal governments pursued investigations, and some jurisdictions even enacted legislation aimed at curbing the Klan’s activities, such as anti-mask laws. These legal challenges made it more difficult for the Klan to operate and instigated a steep decline in membership.

Socially, the tides of racial and ethnic tolerance began shifting, albeit slowly. Active opposition from civil rights organizations rallied public sentiment against the Klan’s hateful ideologies, and their efforts to challenge discriminatory policies started to gain traction. Concurrently, the economic prosperity waned with the onset of the Great Depression, shifting national priorities from cultural divisiveness to economic survival, further lessening the Klan’s appeal.

Finally, the inherent weaknesses in the Klan’s organizational structure—relying heavily on fear and intimidation, without a sustainable, positive agenda—meant that once their external threats diminished and their inner workings were exposed, their ability to attract and maintain a broad membership quickly dissolved. The internal fractures within its ranks, along with the decline in public interest, effectively dismantled much of its national influence by the end of the decade.