The Civil War (1861–1865) profoundly altered the economic balance between the Northern and Southern states. Before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, these regions had already diverged in terms of industrial capacity, labor systems, and financial resources. By the war’s end, factories in the North had surged to meet military demands, while the agrarian South grappled with ruined infrastructure and a collapsed labor structure. In the ensuing decades, the United States transformed into a more unified economic entity, but the transition was neither smooth nor uniform across regions.

In this article, we will delve into the economic changes that shaped both the Union and the Confederacy from the pre-war era through the Reconstruction period and beyond. We will explore how the North leveraged its industrial might to fund and supply the war effort, how the South’s reliance on slave labor hindered its ability to adapt, and how both regions managed the monumental costs of war, currency fluctuations, and post-war rebuilding efforts. By examining factors such as inflation, labor shifts, and federal policies, we can better understand the far-reaching consequences of the Civil War on American commerce and society. Let’s take a closer look at the roots, realities, and ramifications of this pivotal time in U.S. history.

Pre-War Economic Landscape

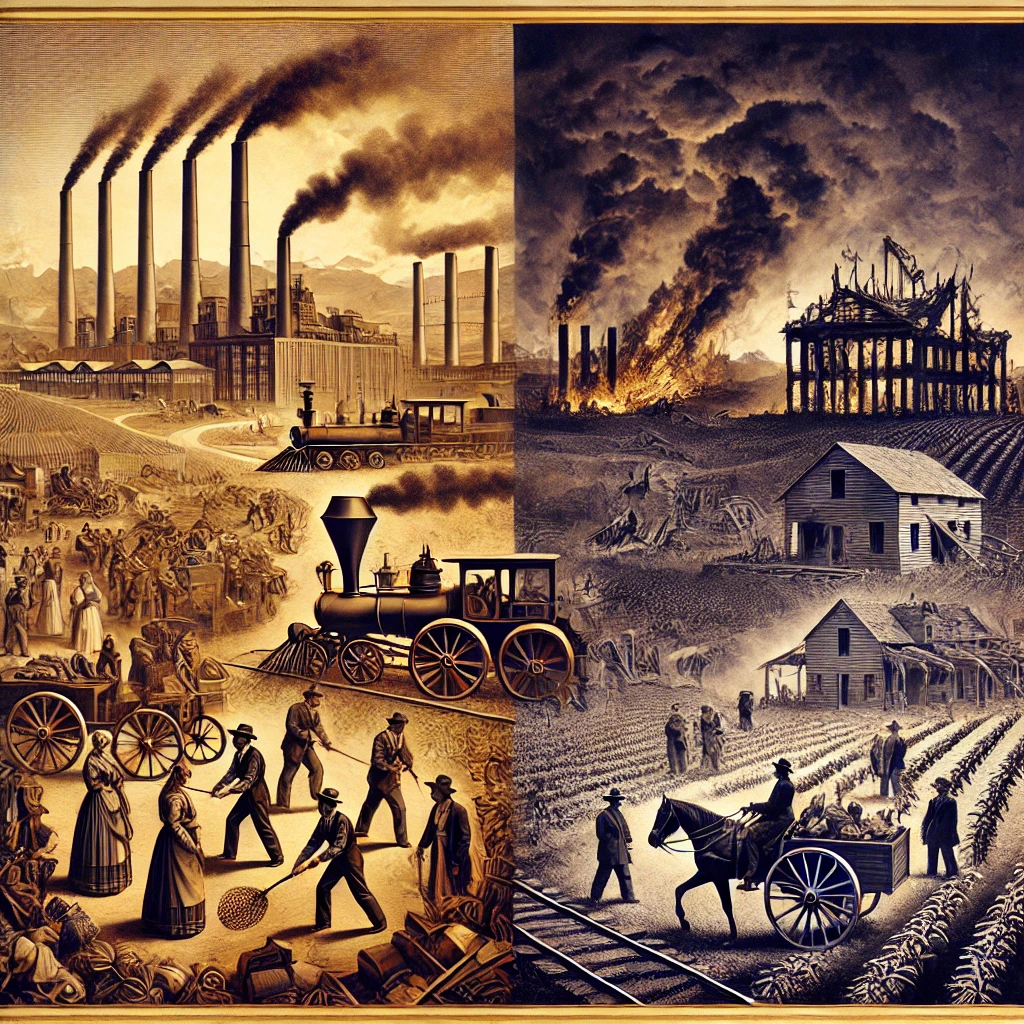

Before the Civil War began, the North and the South exhibited starkly different economic structures. The North had embarked on a path of rapid industrialization: factories, railroads, and a growing population of wage laborers were all hallmarks of a region embracing the Industrial Revolution. Cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia bustled with activity, fueled by a strong financial sector and steady immigration. This influx of immigrants provided the labor needed to power factories, textile mills, and other manufacturing ventures. Railroads and canals crisscrossed Northern states, enabling faster movement of goods and people. The North’s diversified economy wasn’t entirely industrial—there was plenty of farming in states like Pennsylvania and Ohio—but manufacturing and commerce were rapidly taking the lead.

By contrast, the Southern economy centered on agriculture—especially cotton. Known as “King Cotton,” this cash crop dominated Southern exports and generated wealth for plantation owners. However, the prosperity was built on the forced labor of enslaved African Americans. This reliance on slave labor discouraged the development of manufacturing and led to fewer large cities and industrial centers. Banks in the South often focused on financing land and slave purchases rather than funding industrial projects. With minimal railroad infrastructure relative to the North, the South also lagged in efficient transportation networks.

When tensions over slavery erupted into war, these divergent economic systems set the stage for major challenges on both sides. The North’s industrial base and robust financial networks positioned it to better handle the costs of war. Meanwhile, the South’s dependence on a single crop and enslaved labor force would soon be upended by the Union blockade, battlefield losses, and emancipation. These foundational economic differences are essential to understanding how the Civil War would unfold and how each region would eventually cope with its aftermath.

Wartime Industrial Boom in the North

Once the Civil War commenced, the North’s industrial might became a decisive factor. Factories transitioned to the production of uniforms, weapons, ammunition, and other military supplies at an unprecedented pace. Textile mills shifted output toward army clothing, while iron foundries in places like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts ramped up the manufacture of artillery, rifles, and ironclad ships. This wartime demand invigorated businesses, leading to job creation and boosting wages—although inflation often ate into real earnings.

The federal government, under President Abraham Lincoln, worked closely with private industries. War contracts were awarded to factories that could meet the Union Army’s needs, and the government financed these efforts through taxation, borrowing, and the printing of currency known as “greenbacks.” The Legal Tender Act of 1862 helped the Union standardize currency, making transactions easier and unifying the Northern economy. While the increased money supply did fuel inflation, the North’s advanced banking system and diversified economy provided greater stability compared to the South.

Railroads in the North, already more extensive than those in the South, played a crucial role in transporting troops and supplies. The efficient use of rail lines made it possible to reinforce battlefronts quickly and ensured that factories could readily access raw materials like coal and iron ore. In many ways, the war accelerated industrial innovation, leading to technological advancements in weaponry, machinery, and production methods.

The economic ripple effects were significant. The growing demand for industrial output kept factories humming throughout the war. Steel production began to gather momentum, and new inventions—such as improved steam engines—found large-scale use. Industries that supported the war effort were often poised for peacetime expansion. By war’s end, the Northern industrial juggernaut stood on the brink of an era of massive growth, paving the way for the Gilded Age in the late 19th century.

Southern Agriculture Under Strain

While Northern industries saw a boom, Southern agriculture faced devastation. Blockades imposed by the Union Navy significantly curtailed the export of cotton and the import of vital goods like clothing, medicine, and machinery. Because the Confederate economy relied heavily on trade with Europe—particularly for the sale of cotton in exchange for supplies—the blockade effectively choked off the South’s primary revenue stream. Cotton bales stockpiled at ports, unable to reach international buyers, drastically reducing Southern planters’ incomes.

Furthermore, the South’s labor system underwent a dramatic shift during the war. Although enslaved people continued to be forced to work the land, disruptions caused by the conflict, including the movement of Union troops through Southern territories, led to widespread dislocation. Some enslaved individuals escaped to Union lines, where many enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops or sought refuge in Northern cities. Plantations increasingly struggled with manpower shortages, hampering the planting and harvesting of crops. In areas directly affected by combat, farmland was destroyed, livestock was seized or killed, and entire communities were uprooted.

The Confederate government attempted to address these economic pressures by implementing its own currency, known as Confederate notes, and issuing war bonds. However, without the North’s diversified economy or stable financial system, the South quickly experienced rampant inflation. The prices of basic goods soared beyond the reach of ordinary families. Women played a critical role in keeping farms running, often working fields themselves or managing plantation operations, but the overall collapse of the Confederacy’s trade and infrastructure made survival extremely difficult.

By the close of the war, the South was left with a shattered infrastructure and an agricultural sector in disarray. Cotton, once the engine of Southern prosperity, had become a liability, as over-reliance on a single crop and slave labor proved unable to sustain the region in wartime. This dire economic situation would remain a major hurdle in the post-war years.

Inflation and Currency Challenges

Both the Union and the Confederacy faced financial strains that led to inflation, though the impact was far more severe in the South. In the North, the introduction of the greenback made it easier to conduct business and pay troops, but it also increased the money supply considerably. Inflation was noticeable, yet it was relatively controlled thanks to a stronger industrial base, ongoing trade, and a better-organized banking system. The National Banking Acts passed during the war also created a network of nationally chartered banks, providing more consistent financial oversight.

In contrast, the Confederacy’s decision to print vast sums of money without sufficient gold or international support triggered runaway inflation. The Confederate dollar plummeted in value, sometimes requiring thousands of dollars just to buy everyday necessities. As the war dragged on, public confidence in Confederate currency eroded. Some citizens resorted to barter, trading goods and services because money had become practically worthless. This rampant inflation not only harmed individual families but also made it nearly impossible for the Confederate government to keep its own war machine adequately supplied.

Desperate measures, such as impressment (the seizure of goods by the Confederate army), further undermined faith in the government and strained relationships between civilians and the military. While the North did increase taxes and borrowed heavily to finance the war, it had clearer channels of revenue generation—such as tariffs on goods, an expanding industrial economy, and a more stable currency—allowing it to manage inflation more effectively.

The contrast in monetary policies and their outcomes would be one of the lasting lessons of the Civil War period. The North emerged with a stronger federal financial system, while the South’s disastrous experiment with decentralized currency contributed to its downfall.

Labor Shifts and Workforce Changes

One of the Civil War’s most transformative effects was the reshaping of the American labor force. In the North, the war effort prompted a surge in factory employment. The draft took many men off factory floors and farms, but wartime production needs created new jobs, pulling in immigrants and even women to fill workforce gaps. Women worked not just as seamstresses or nurses but also took on roles in munitions factories, railroads, and other industries previously dominated by men. This contributed to an evolving view of women’s capabilities outside the home, though significant gender-based pay disparities persisted.

In the South, the labor system rooted in slavery was irrevocably changed by the war and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. While emancipation did not immediately free all enslaved individuals in the Confederacy, as Union armies advanced, thousands of enslaved people seized the opportunity to gain freedom. After the war, the question of how to incorporate newly freed African Americans into the economic fabric became a pressing concern. Landowners lost their main source of coerced labor, and the Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help former slaves with education, legal rights, and employment. However, systemic racism and lack of resources complicated the Bureau’s efforts.

Sharecropping, which emerged during Reconstruction, became the new agricultural labor framework in many Southern states. Under sharecropping, landowners allowed tenants—often formerly enslaved individuals—to farm their land in exchange for a share of the crop. While this system provided a semblance of autonomy for Black farmers, it often led to debt cycles and economic dependence on landlords. Thus, while the Civil War ended slavery as a legal institution, it did not eliminate economic inequality or create a level playing field for all.

The War’s Immediate Aftermath

When the guns fell silent in 1865, both regions faced a set of daunting challenges. For the North, despite the relative stability of its economy, the sheer cost of the war—estimated at billions of dollars—had led to a significant national debt. Soldiers returning from the frontlines needed jobs, and although industrial expansion was on the horizon, transitioning from a wartime to peacetime economy required careful planning. Nonetheless, Northern cities largely escaped physical destruction. Factory owners quickly pivoted from wartime manufacturing to consumer goods, while railroad companies expanded lines westward, seeking new markets and resources.

The South, however, was physically and economically ravaged. Major cities like Atlanta and Richmond lay in ruins. Fields were burned and livestock decimated, making immediate agricultural recovery nearly impossible. The loss of enslaved labor also meant plantation owners had to adapt to a free-labor system they had long resisted. Southern families struggled to feed themselves amidst a devastated infrastructure. Additionally, Confederate war bonds and currency became worthless, wiping out savings and leaving many with no financial safety net.

At the national level, new amendments to the Constitution—particularly the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery—redefined the legal and social landscape. But these changes did not bring instant economic relief. Debates raged in Congress over how best to rebuild the South and integrate millions of newly freed African Americans into society. While the end of the war signaled a monumental shift toward unity, it was clear that the path forward involved more than battlefield victories. Economic policies, reconstruction plans, and societal attitudes would play an equally critical role in shaping the post-war nation.

Reconstruction: A New Economic Era

Reconstruction (1865–1877) was the federal government’s attempt to reintegrate and rebuild the former Confederate states while extending legal protections to newly freed African Americans. Economically, Reconstruction efforts included measures like the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which aimed to provide financial aid, education, and job placement. However, federal initiatives often met resistance from white Southern landowners who resented Northern interference and feared the empowerment of formerly enslaved people.

Northern investors saw opportunities to modernize the Southern economy. Some capital flowed into the region to rebuild railways, open factories, and tap into raw materials like timber and minerals. Still, much of the South remained dominated by agriculture. Sharecropping and tenant farming replaced slavery as the primary labor system, which, while offering a measure of independence, often locked both Black and poor white farmers into perpetual debt. With few industries to provide alternative employment, many Southern communities lagged far behind the North in economic recovery.

During this period, the North benefited from an influx of European immigration, robust industrial growth, and westward expansion facilitated by the Homestead Act and the continued construction of the transcontinental railroad. Iron, steel, and railroad companies thrived, fueling the rise of great industrialists who would dominate the late 19th-century economy. Tariffs remained relatively high, which protected Northern manufacturers but sometimes hurt Southern and agricultural interests.

Though Reconstruction policies attempted to create a more balanced national economy, real transformation in the South was slow. Discriminatory Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws undermined the mobility and economic advancement of African Americans. Despite these barriers, some progress occurred: a small Black middle class emerged in urban areas, and historically Black colleges and universities were founded, creating a legacy of education that would pay dividends in future generations. Yet the broader regional disparity between North and South persisted.

Long-Term Consequences for the North

In the decades after the Civil War, the Northern economy rode a wave of industrialization, giving rise to the period often called the Gilded Age (roughly 1870–1900). Railroad expansion knitted the country together, stimulating steel production and opening new markets for manufactured goods. Tycoons like Andrew Carnegie in steel and John D. Rockefeller in oil exemplified the era’s rapid wealth accumulation. Labor unions also began to form as factory workers sought better wages and safer working conditions, setting the stage for major labor movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Investment capital increasingly flowed into Northern enterprises, and with each new industrial innovation—whether in the textile, steel, or automotive sector—new jobs and fortunes were made. Cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland grew rapidly, fueled by factories and an ever-increasing urban population. This growth, however, was not without challenges. Overcrowded slums, harsh working conditions, and rampant political corruption tarnished the era’s gilded surface.

Nevertheless, the Civil War had laid the foundation for the North’s economic ascendancy. Federal policies such as the Morrill Tariff protected domestic manufacturing from foreign competition, while the National Banking Acts brought greater coherence to the financial system. The war had also fostered a culture of innovation—government contracts during the war had funded research and development in armaments, railroads, and other technologies that now spilled over into the private sector. By the turn of the century, the United States had emerged as one of the world’s leading industrial powers, with the North serving as its primary economic engine.

Long-Term Consequences for the South

Rebuilding the Southern economy proved far more challenging. The initial devastation—ruined farms, lost slave labor, destroyed railroads—was only the beginning. Even as the South gradually rebuilt infrastructure, it remained heavily reliant on agriculture. Cotton continued to be a mainstay, but competition from foreign cotton producers and the exploitative nature of sharecropping limited profits. Tobacco, rice, and sugarcane were also cultivated, yet these staples yielded meager returns without significant industrial or financial backing.

Industrialization did come to some parts of the South, particularly in textile mills built near fast-flowing rivers and in areas with abundant natural resources like coal and iron (e.g., Birmingham, Alabama, sometimes called the “Pittsburgh of the South”). But overall, the pace of industrial growth remained slow compared to the North. By the late 19th century, many Southern leaders called for a “New South” that embraced modern industry, diversification, and economic integration with the rest of the nation. Prominent voices like Henry Grady urged Southerners to reduce their dependence on cotton, invest in factories, and attract Northern capital.

While some progress was made, systemic problems persisted, including racial segregation, limited access to quality education, and underdeveloped infrastructure. Legal discrimination and lynching terrorized Black communities, deterring entrepreneurs and inhibiting overall social mobility. Many white landowners remained skeptical of modernization, clinging to the traditions of large-scale agriculture.

Despite these roadblocks, pockets of economic advancement did emerge. Rail lines expanded, small industrial centers appeared, and urban areas like Atlanta and New Orleans grew in commercial significance. However, the region’s overall recovery would take generations, and even today, economists and historians trace the economic disparities between different parts of the country back to the Civil War and Reconstruction era. The war’s end brought freedom to millions but also a challenging economic reality that shaped how the South developed—and, in many ways, struggled—well into the 20th century and beyond.

Conclusion

The Civil War left a profound economic imprint on both the North and the South. For the North, the conflict accelerated industrial growth, spurred technological innovation, and led to the establishment of a more centralized federal financial system. Government contracts and wartime demands stimulated factory output, fueling a machine that would power the United States toward global industrial leadership by the early 1900s. The post-war decades witnessed an influx of capital, labor, and inventions that defined the Gilded Age, complete with its blend of remarkable prosperity and stark social inequalities.

For the South, the war resulted in significant destruction, the collapse of its primary labor system, and a decline in the once-lucrative cotton trade. Reconstruction efforts attempted to rebuild the region and integrate newly freed African Americans into the economy, but systemic racism, limited infrastructure, and a reliance on sharecropping stunted progress. Although some industrial strides were made, the South largely lagged behind the North in economic development for decades, a disparity that historians continue to examine in relation to policy decisions, racial oppression, and the challenges of transitioning to a free labor system.

Understanding the Civil War’s economic consequences provides critical insight into why the United States looks the way it does today. The diversification and expansion of Northern industries laid the groundwork for a modern, more centralized economy, while the South’s struggles highlighted the limitations of an agrarian-based system rooted in forced labor. As we reflect on this era, we see that economic transformations do not occur in isolation; they intertwine with social, political, and cultural forces that shape a nation’s destiny. The Civil War was both an ending and a beginning—closing one chapter of American history and igniting another that would redefine the country’s economic landscape for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How did the Civil War impact the industrial capacity of the Northern states?

The Civil War significantly boosted the Northern states’ industrial capacity as they ramped up production to meet military needs. Before the war, the North was already more industrialized than the South, but the conflict accelerated this trend. Factories in the North produced guns, ammunition, uniforms, and other essential military supplies at an unprecedented pace. The demand for war supplies led to technological advancements and increased efficiency within Northern industries. Additionally, the infrastructure in the North, such as railroads and telegraph lines, expanded rapidly to improve logistics and communication during the war. Overall, the industrial prowess of the North was enhanced greatly, laying the foundation for the United States to become a world industrial leader in the following decades.

2. What economic challenges did the Southern states face after the Civil War?

The Southern states faced immense economic challenges following the Civil War, largely due to the destruction of infrastructure and the collapse of their labor system. With the abolition of slavery, the South lost its primary labor force, which had been the backbone of its agrarian economy. Plantation owners struggled to adapt to the new reality of wage labor, and many lands were left untended. Additionally, the war had devastated Southern infrastructure, with railways torn up and cities in ruins. The economic stagnation was exacerbated by the loss of capital as Southern states had invested heavily in Confederate currency, which became worthless after the defeat. With limited industrial capacity almost no financial resources, and a drastically altered labor system, the South faced a daunting period of economic recovery and restructuring in the post-war years.

3. How did the Civil War influence trade and commerce between the North and South?

During the Civil War, trade and commerce between the North and South were severely disrupted. The Union’s blockade of Confederate ports aimed to cut off supplies to the South and cripple its economy. This blockade greatly limited the South’s ability to export cotton, its main economic staple, to international markets. Conversely, the disruption of Southern agriculture pushed the Northern states to develop and expand their agricultural sectors to compensate for the loss of Southern goods. After the war, the North and South had to rebuild their economic relationships on new terms. The Northern states were in a stronger economic position, leading to a more dominant role in setting the terms for trade and commerce in the reunited country. Building trade networks and commerce interactions anew demanded significant effort and changes to both regions’ economic strategies.

4. What were the long-term economic outcomes of the Civil War for the United States?

The Civil War had several long-term economic outcomes for the United States, influential in the nation’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse. First, the industrial boom in the North laid the groundwork for rapid industrialization in the decades following the war. The focus on manufacturing and innovation fueled economic growth and helped establish the United States as a major economic force globally. In contrast, the South faced a lengthy and painful reconstruction process but eventually began diversifying its economy away from a purely agrarian focus. The war also led to changes in taxation and financial policy, as the federal government took a more active role in economic affairs, including the introduction of the first income tax to fund the war effort. Moreover, veterans returning home spurred westward expansion and development, shaping a new economic era for the entire nation.

5. How did the Civil War impact labor systems in both the North and South?

In the North, the Civil War exacerbated labor shortages due to the draft, which pulled many working men into military service. However, this period also saw an influx of immigrant laborers, who filled the workforce gaps and contributed significantly to industrial output. The labor system adjusted by adopting new machinery and technologies to maintain productivity with fewer workers, setting a precedent for mechanized labor that continued after the war. In contrast, the South faced a dramatic upheaval of its labor system. The end of slavery left former slaves and their former owners in a state of uncertainty. Sharecropping and tenant farming became common practices as a temporary solution, yet these systems perpetuated economic disparity and social hierarchy. Indeed, the post-war labor reorganization in the South was a slow and struggling shift toward a cash economy with wage labor, influenced by racial and social tensions that lingered deeply into the 20th century.