The Roaring Twenties is often remembered as an era of unprecedented economic growth, jazz music, and cultural dynamism in the United States. But after the stock market crash of 1929, the country slipped into the Great Depression, a time of severe unemployment and economic hardship. During this challenging period, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced a series of government programs known as the New Deal, aiming to revive the economy and offer direct relief to struggling Americans. Among the most impactful and enduring of these initiatives was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). While the CCC is frequently praised for its role in providing employment to millions of young men, its significance in environmental protection and conservation cannot be overstated. In this article, we will explore how the CCC contributed to preserving America’s natural resources, laid groundwork for modern environmental efforts, and left a lasting legacy on the American landscape.

Setting the Stage: From the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression

The Prosperity of the 1920s

The 1920s in America, also known as the Roaring Twenties, brought about significant changes in society and culture. A booming stock market, technological advancements like the radio and the automobile, and a wave of consumer culture fueled a sense of optimism. However, this rapid prosperity was built on unstable economic practices. Many investors took on massive debts to buy stocks, believing the market would keep rising indefinitely. Consumer debt soared as well, with people purchasing goods on credit and banks handing out loans with little scrutiny.

The Crash of 1929 and the Onset of the Great Depression

The stock market crash of October 1929 signaled an abrupt end to the era’s exuberance. When panic set in and investors sold off stocks en masse, prices plummeted. Banks that had invested heavily or offered risky loans suffered immediate losses, leading to widespread bank failures. Businesses also folded under financial pressure, and millions of Americans lost their jobs. By the early 1930s, the Great Depression gripped the nation with unemployment rates exceeding 20%. This was a drastic shift from the carefree days of the Roaring Twenties and left the country seeking new solutions to unprecedented challenges.

The Birth of the Civilian Conservation Corps

FDR and the New Deal

In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was elected president. He inherited an economy on the brink of collapse and a population desperate for work and hope. In response, FDR launched the New Deal, a sweeping set of government programs designed to stabilize the economy, reform financial systems, and provide direct relief to Americans. One of the earliest and most successful components of the New Deal was the Civilian Conservation Corps, created by Executive Order 6101 on March 31, 1933.

The Vision Behind the CCC

Roosevelt believed strongly in both the value of hard work and the importance of conserving the nation’s natural resources. The idea was elegantly simple: hire unemployed young men to work on environmental projects across the country. This approach would serve a dual purpose—providing jobs for those in need while preserving and enhancing natural lands that had been depleted by overfarming, logging, and other industrial activities. By employing men aged 17 to 28, the government also aimed to direct restless, unemployed youth toward constructive and healthy pursuits.

CCC Structure and Daily Life

Enrollment and Organization

At its peak, the CCC enrolled roughly 300,000 men at one time, and over its nine-year lifespan (1933–1942), more than 3 million young men participated in the program. Enrollees were generally required to send a portion of their monthly pay back to their families, ensuring that the economic benefits of the program trickled into households across the country. This arrangement not only offered financial relief to struggling families but also boosted local economies.

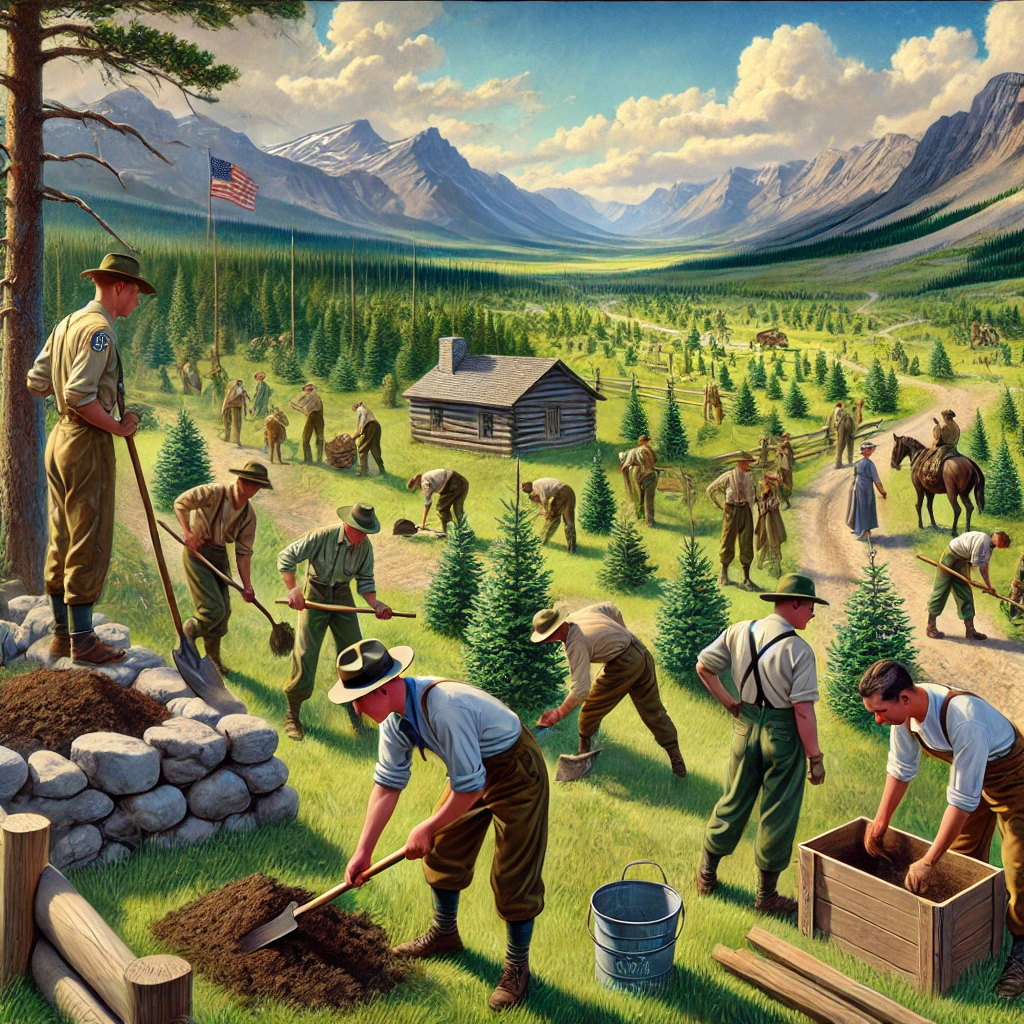

The CCC operated under the War Department initially, with assistance from other agencies like the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. Enrollees lived in camps often run by Army Reserve officers. Although it was a civilian program, the daily routines borrowed from military discipline, which helped maintain order and organization.

Life in the Camps

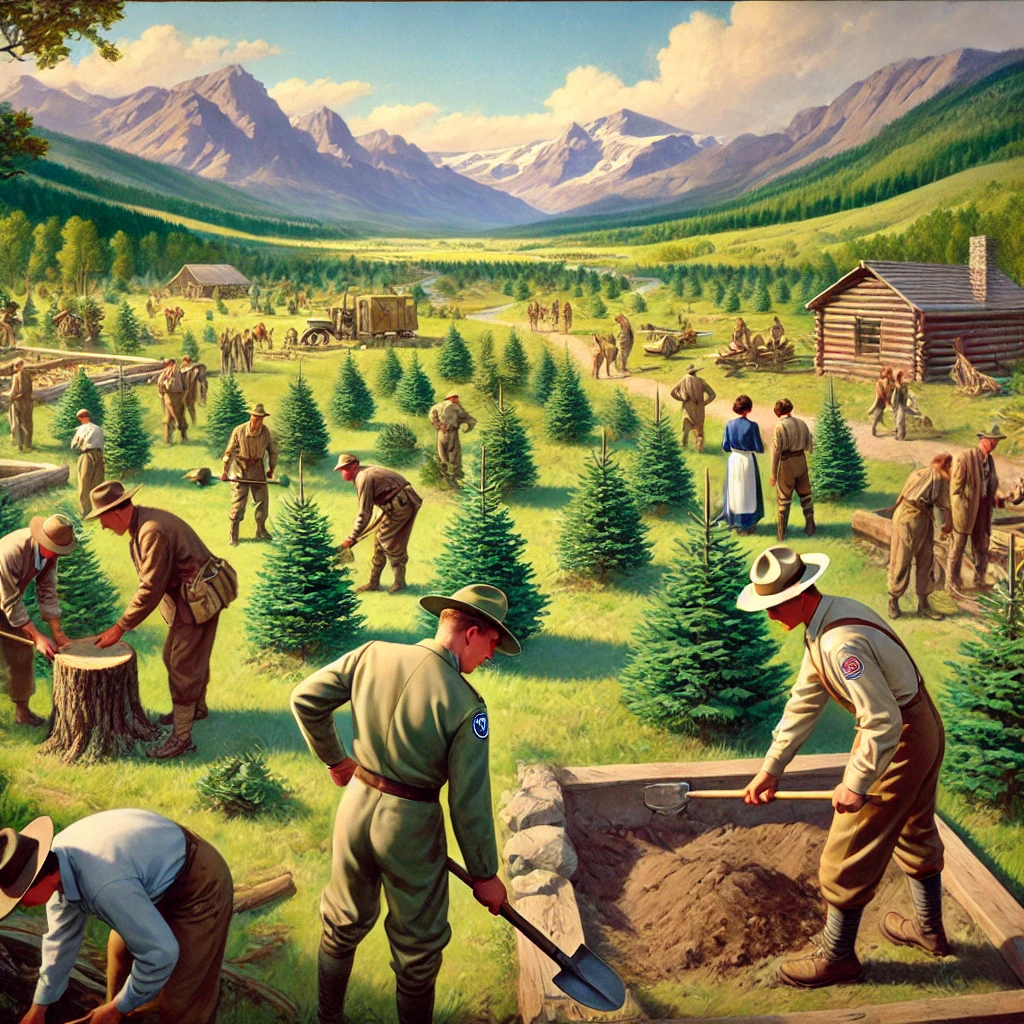

A typical CCC camp could house about 200 men, who lived in barracks-style quarters. Days began early, with a wake-up call often before dawn. After breakfast, the men would head out to work sites such as forests, national parks, and farmland where they planted trees, built firebreaks, fought soil erosion, and developed park facilities. In the evenings, many CCC camps offered educational classes, teaching everything from literacy and arithmetic to vocational skills like carpentry and mechanics. While discipline was strict compared to civilian life, many enrollees appreciated the newfound sense of camaraderie and purpose. They were not just earning a wage—they were actively transforming the nation’s natural landscapes.

Core Environmental Initiatives of the CCC

Reforestation Efforts

One of the most significant contributions of the CCC was reforestation. Decades of unregulated logging, coupled with exploitative agricultural practices, had left large swaths of the country barren and prone to soil erosion. The CCC stepped in, planting an estimated 3 billion trees during its existence. These new forests helped stabilize soil, improve watersheds, and restore wildlife habitats. Many of the forests we see today, especially across the Midwest and Northeast, owe their existence to the seeds planted by CCC workers.

Soil Erosion Control

The 1930s were infamous for the Dust Bowl, a catastrophic environmental disaster primarily affecting the Great Plains. Years of drought and poor farming practices had turned fertile soil into dust, which blew across the region in massive clouds. Farms were devastated, leading to mass migrations and worsened economic hardship. To combat this, CCC crews built terraces, planted windbreaks, and worked on soil conservation projects to anchor topsoil and prevent further erosion. These efforts were crucial in restoring arable land and reducing the impact of dust storms.

Wildlife and Parks Development

Beyond addressing pressing issues like deforestation and soil erosion, the CCC played an integral role in developing and maintaining state and national parks. Workers constructed trails, roads, shelters, and recreational facilities—many of which are still used today. They also helped manage wildlife populations by building check dams and restoring habitats to support fish and bird species. The emphasis on creating accessible, well-maintained parks contributed to a new appreciation for outdoor recreation among Americans, setting the stage for modern national park and state park systems.

Impact on National Parks and Forests

Building Park Infrastructure

Before the CCC, many national parks suffered from limited or nonexistent infrastructure. Visitors often struggled with rough roads, lack of visitor centers, and inadequate camping facilities. CCC projects addressed these challenges by constructing trails, bridges, and buildings. For example, at the Grand Canyon in Arizona, CCC men built new trails and rest areas that made the park more accessible to travelers. In parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone, crews developed campgrounds and ranger stations, laying the groundwork for the thriving tourism industry we see today.

Fire Prevention and Management

Forest fires had long been a threat to America’s woodlands, so another vital CCC responsibility was fire prevention and management. Crews dug firebreaks—cleared strips of land intended to stop or slow a fire’s spread—throughout national forests. They also built watchtowers and roadways that enabled quicker response times when fires did occur. In addition, CCC enrollees often served as first responders to wildfires, tackling blazes before they spiraled out of control. Their work helped protect countless acres of forest and set standards for modern wildfire management techniques.

Educational Outreach

The CCC’s presence in national parks wasn’t just about manual labor. It also created new opportunities for educational outreach. As facilities like visitor centers and museums were constructed, park rangers could more effectively educate the public about local ecosystems, wildlife, and the importance of conservation. This public-facing aspect of CCC work fostered a growing culture of environmental awareness that continued even after the program ended.

The Social and Economic Benefits

Employment and Skill Building

From an economic perspective, the CCC was a lifeline for millions of families. Each enrollee was paid around $30 a month, a significant amount at the time—especially when much of it was sent home to parents, spouses, or siblings. Beyond the paycheck, CCC men learned valuable vocational skills like carpentry, masonry, and mechanics, which made them more employable when they left the corps. Some also discovered a passion for forestry, wildlife management, or outdoor recreation, shaping their future careers and fueling a wider interest in conservation-related fields.

Strengthening Communities

The positive effects of the CCC rippled out into local communities. Small towns near CCC camps saw an influx of economic activity from camp-related spending, including the purchase of food, tools, and other supplies. In many cases, CCC projects provided infrastructure improvements—like new roads and flood control systems—that benefited local residents long after the camps closed. This not only boosted morale during a difficult time but also created tangible assets that contributed to long-term economic recovery.

Inclusivity and Challenges

While the CCC primarily enrolled young, unmarried men, there were also separate programs for veterans of World War I and for Native American men, who worked on reservations under the supervision of the Office of Indian Affairs. However, the program did face criticism for its lack of inclusivity. African American enrollees were segregated into separate units, a reflection of the broader social and institutional racism of the era. Although African American participants did gain employment and skills, their experiences highlight the CCC’s limitations in addressing the full breadth of racial inequalities present in the 1930s.

Long-Term Environmental Impact

Foundations of Modern Conservation Policies

The successes of the CCC laid the groundwork for future federal environmental policies. Many of the techniques pioneered by the CCC—like large-scale tree planting, building strategic firebreaks, and implementing erosion control measures—became part of standard conservation practices. Furthermore, the program’s popularity and visible results bolstered public support for government involvement in environmental protection, paving the way for later legislation such as the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act (1935) and, eventually, the Clean Air Act (1963) and Endangered Species Act (1973).

Evolving Public Attitudes

Before the CCC, conservation was not a universally shared priority. The late 19th and early 20th centuries had witnessed the rise of the conservation movement through figures like Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir, but awareness was still relatively limited among the general public. The CCC changed that by bringing ordinary citizens—especially young men—into direct contact with nature. They built trails in places like the Blue Ridge Mountains, Great Smoky Mountains, and the Pacific Northwest, working alongside forest rangers and other conservation professionals. This hands-on experience cultivated a respect and appreciation for the environment that many enrollees carried into the rest of their lives. As these men returned to civilian life, they shared their experiences, encouraging a broader cultural shift toward valuing America’s natural heritage.

The End of the CCC and Its Lasting Legacy

World War II and Program Dissolution

Despite its popularity and successes, the CCC’s operations wound down in the early 1940s. As the United States entered World War II, federal funding and national priorities shifted. Defense production took center stage, and many young men left for military service. In 1942, Congress ended the CCC as part of broader budget cuts and a need to redirect resources toward the war effort. By that point, the CCC had accomplished an extraordinary amount: millions of trees planted, hundreds of parks improved, miles of trails built, and an entire generation given invaluable job training and a renewed sense of purpose.

Enduring Physical and Cultural Marks

Today, we can still see the impact of the CCC in national parks, forests, and state parks across the country. You might hike on CCC-built trails or camp in facilities originally constructed by CCC enrollees. Stone lodges, picnic shelters, and cabins crafted by CCC workers remain cherished features of many parks, their rustic architecture blending seamlessly with the natural surroundings. In a broader cultural sense, the CCC fostered a stronger environmental ethos in American society. It demonstrated the effectiveness of direct government intervention in both providing work relief and improving natural resources—a model that continues to influence public service and conservation programs.

Modern Echoes: AmeriCorps and Conservation Corps

Although the CCC ended decades ago, its influence can be seen in modern programs like AmeriCorps and state-level conservation corps. These initiatives use similar approaches—paying volunteers or small stipends to engage in service projects, including education, disaster relief, and environmental conservation. These programs echo the CCC’s core principles of work relief and stewardship, reflecting the enduring idea that investing in human capital and natural resources can provide profound benefits to society.

Lessons Learned and Relevance Today

Balancing Economic Recovery and Environmental Stewardship

The CCC offers a powerful historical example of how a nation can tackle economic despair and environmental degradation simultaneously. By tying employment programs to the improvement of natural resources, the United States invested in both people and the environment. This holistic approach continues to be relevant, especially in discussions about “green jobs” and sustainable economic development.

Community Engagement and Education

Another key lesson from the CCC is the value of community engagement. The corps provided a structured environment where enrollees not only worked but also received education and training. Modern conservation efforts can benefit from similarly holistic approaches, combining environmental projects with robust educational programs to build the next generation of environmental leaders.

Preparedness and Adaptability

Environmental challenges in the 21st century—like climate change, wildfires, and pollution—echo some of the difficulties faced during the Dust Bowl era. The CCC’s capacity to organize large-scale conservation projects in a short period underscores the importance of preparedness and adaptability. Governments, communities, and organizations that can mobilize resources quickly to address environmental crises stand a better chance of preventing or mitigating long-term damage.

Conclusion

The Civilian Conservation Corps stands as a remarkable chapter in American history—a dynamic intersection of social policy, economic relief, and environmental conservation. Born out of the crisis of the Great Depression, the CCC addressed immediate financial hardships by employing millions of young men. At the same time, it planted billions of trees, curbed soil erosion, developed national parks, and created fire prevention infrastructure that protected forests for generations to come. This blend of workforce development and ecological stewardship has left a lasting imprint on both the American landscape and the nation’s collective consciousness.

When you step onto a trail in a national park or drive down a scenic byway flanked by towering forests, you may well be witnessing the labor and legacy of the CCC. The cabins, bridges, and lodges—built with care and often from local materials—stand as timeless reminders of what collective effort can accomplish. Equally important is the program’s role in shaping attitudes toward conservation. The CCC showed that protecting the environment does not have to come at the expense of economic progress—instead, the two can complement each other in profound ways.

For students of social studies and American history, understanding the CCC provides a multifaceted lesson. It reveals how government intervention during times of crisis can spark innovation, how large-scale conservation projects can repair depleted ecosystems, and how a spirit of service and stewardship can permeate across generations. From the Roaring Twenties’ exuberance to the desperation of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps offers a vital example of resilience, cooperation, and the enduring power of collective action in preserving our natural world. It remains a shining testament to how America, when faced with adversity, can generate forward-thinking solutions that stand the test of time.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and how did it contribute to environmental protection?

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of the first New Deal programs implemented by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933. It aimed not only to provide jobs during the height of the Great Depression but also to tackle America’s pressing environmental concerns. The CCC helped shape America’s green legacy by employing young men in projects that conserved and developed the country’s natural resources. The corps worked extensively on projects such as reforestation, soil erosion prevention, and the development of national and state parks.

Participants in the CCC planted nearly 3 billion trees, constructed more than 800 state parks, and built thousands of miles of hiking trails. By focusing on conservation, the CCC didn’t just provide immediate relief to unemployed youth but also ensured the long-term preservation of the nation’s environmental resources. The experience also educated its members about the environment and sustainable practices, some of whom later advocated for or worked in conservation-related fields.

2. How did the Great Depression influence the formation of the CCC and its environmental initiatives?

The Great Depression was a period of massive economic decline that led to widespread unemployment and poverty. In response, the federal government, under Franklin D. Roosevelt, launched an array of programs under the umbrella of the New Deal to uplift the economy and provide relief to suffering Americans. The CCC was one of these pivotal programs designed to address both economic and environmental needs.

At the time, the United States faced severe ecological challenges, including deforestation, soil erosion, and desertification, issues that only exacerbated economic woes by affecting agriculture and rural livelihoods. By creating the CCC, the government was able to deploy unemployed young men to work on projects that not only provided them with income and skills but also directly addressed the nation’s environmental crises. This dual-focus on employment and environmental conservation was crucial in fostering a legacy of sustainability and ecological awareness in the United States.

3. In what ways did the CCC’s work set the stage for future environmental policies in the United States?

The CCC was instrumental in shaping the direction of future environmental policies in the United States by planting the seeds of conservation consciousness. Many of the CCC projects laid critical groundwork for conservation and infrastructure upon which future environmental policies would build. This program was a tangible demonstration of how labor-intensive, environmentally-focused initiatives could achieve dual goals: providing necessary employment and preserving national resources.

The success of the CCC showed policymakers that systematic government intervention in environmental projects could yield substantial benefits, thus setting a precedent for future federal involvement in environmental protection. Many CCC alumni went on to hold positions of influence, spreading the conservation ideals they learned during their service. Furthermore, the public works accomplished by the CCC became the backbone for later environmental legislation and the establishment of robust national and state parks systems.

4. What role did education and skill-building play in the CCC’s environmental efforts?

Education and skill-building were core components of the CCC experience, providing participants with much more than just immediate employment. The program was designed to offer young men training and work experience that would benefit their future career prospects. In the process of carrying out conservation tasks, enrollees learned valuable practical skills related to forestry, firefighting, and land management, among other trades. This educational facet of the CCC was particularly influential in instilling a respect for environmental stewardship among its members.

The vocational training received through the CCC not only empowered participants by expanding their employability in the depressed job market of the time but also fostered a generation of individuals more attuned to the principles of conservation and sustainability. Many of these trained personnel became ardent advocates for the environment, contributing to environmental awareness and policy advancements long after their tenure in the CCC had ended.

5. How has the legacy of the CCC influenced modern conservation efforts and America’s approach to environmental issues today?

The legacy of the CCC continues to echo through modern conservation efforts and America’s approach to environmental issues. The concept of engaging citizens, particularly the youth, in conservation activities is still a critical strategy today, as seen in various service corps and environmental organizations. The CCC not only set a historic benchmark for government-funded environmental programs but also demonstrated that public investment in ecology can bring economic, social, and environmental dividends.

Today’s conservation projects owe much to the groundwork laid by the CCC. The widespread tree planting, park creation, and resource management strategies pioneered during the 1930s have become integral to contemporary environmental protection frameworks. The CCC’s integration of workforce development with environmental conservation also highlights an ongoing understanding of the importance of education and skills in achieving sustainable environmental goals.